A perfectly tempoed coming-of-age Western, with clear meditations on the difference between boys and men, between crime and moral fortitude…and between murder and justice.

By Paul Mavis

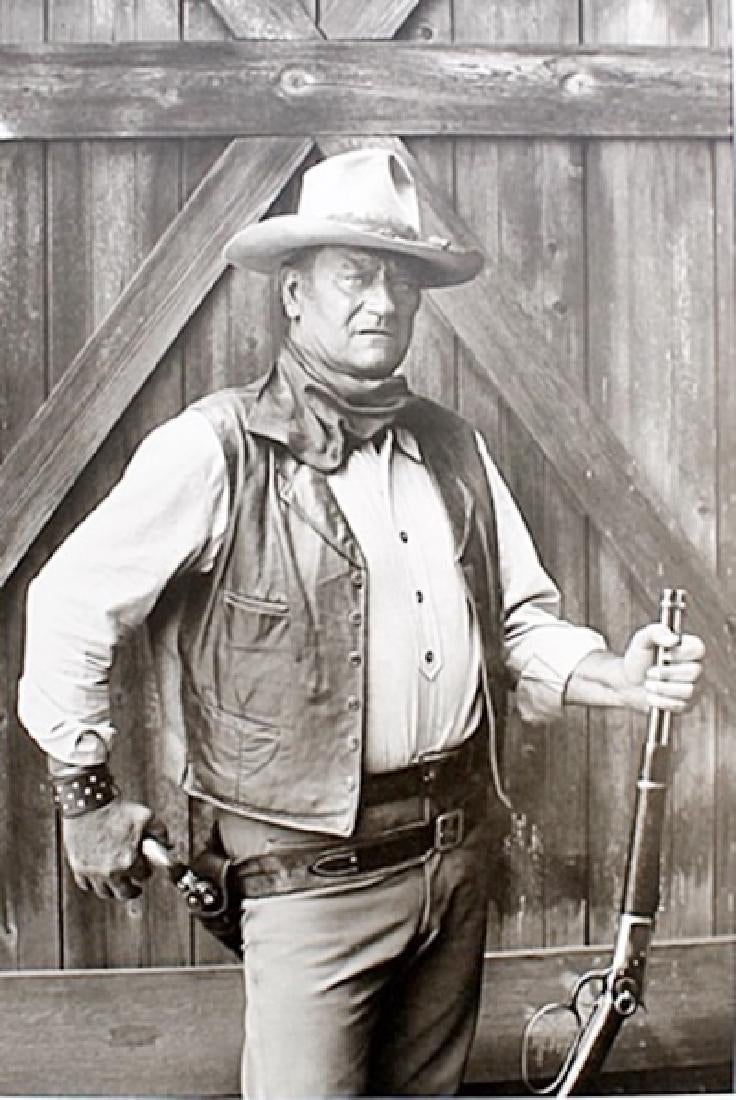

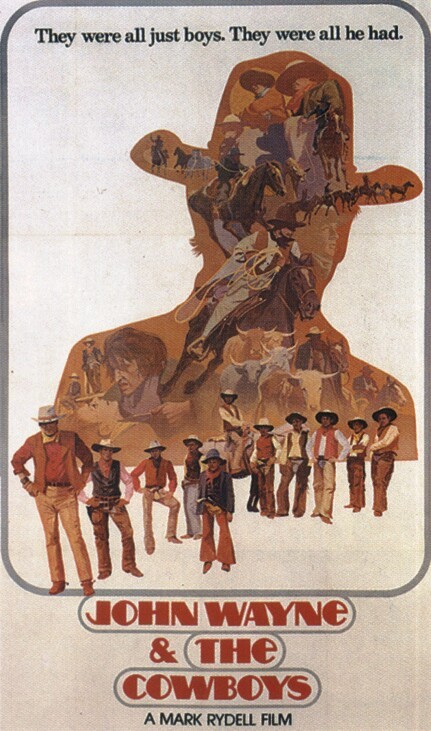

Available on various Warner Bros. Blu-ray discs (I’m a particular fan of the triple feature including it with The Green Berets and The Searchers), The Cowboys, written by Irving Ravetch and Harriet Frank, Jr., and directed by Mark Rydell, was a huge late career hit for the Duke, John Wayne, and one of his personal favorites. Filled with exciting adventure, gentle humor, and most importantly, a moral worthy of the best Western fables, The Cowboys allowed Wayne to give yet another deceptively simple but technically complex performance, lending The Cowboys an emotional gravity it would never have had, had Rydell not eventually relented on casting him in the part (liberal Rydell hated his politics…and wound up loving Wayne). It’s required viewing for Wayne and Western fans.

Click to purchase this John Wayne Triple Feature Blu-ray at Amazon.

Your purchase helps pay the bills at this website!

Aging rancher Wil Andersen (John Wayne) is in a bind: gold fever has struck the county, and all his ranch hands have left right before they’re to take 1,500 head of cattle on a 400 mile drive. Unable to find replacements, and unwilling to put his bills off onto credit, Andersen reluctantly tries the local one-room school house in hopes of finding some young cowpokes. But after observing the childish pranks of the children there, he gives up that idea, and returns home.

A few days later, he and his wife Annie (Sarah Cunningham) awake to the sounds of the school boys waiting outside, hoping to find employment. Encouraged by Annie, Wil gives the boys a test—riding a wild bronc for 10 seconds—figuring that none of them will stay on. But one by one, the plucky youngsters, none older than fifteen and more than a few quite younger than that, manage to hang on, impressing Wil.

Out of options, he later agrees to let the boys ride along, as long as they know how difficult the journey is going to be. Further unsettling Wil (he prefers to ride with men he knows) is the substitute chuck wagon cook, Jedediah Nightlinger (Roscoe Lee Browne), a black man who Wil respects…when he knows the recipe for apple pie, and when he demands more money than Wil’s offering to pay. The unlikely group sets out on their cattle drive, full of unrealistic high spirits.

RELATED | More reviews of Westerns

After the initial shock of the back-breaking work sinks in, the cattle drive turns into a rite of passage for the boys, who bond over their first surreptitious drunk together, and who learn from Wil’s example that it is indeed a hard world where nothing comes easy or free. However, none of these physical hardships come close to the life-and-death danger posed by Asa Watts (Bruce Dern) and his gang.

Initially trying to get jobs with Wil, Asa is found out in a lie and his services are rejected by the scornful Wil. Criminals newly out of jail, Asa and his gang secretly shadow the drive until they’re found out by Dan (Nicolas Beauvy), a bespectacled young boy who Asa threatens with death if he spills the beans to Wil. When Jedediah falls behind with a broken wheel on the chuck wagon, Asa makes his move for the cattle, engaging Wil in vicious fight…which will set in the motion the boys’ maturation into men.

There was a lot of controversy when The Cowboys came out in 1972, particularly from liberal critics who were fed up with the violence in John Wayne’s films (they didn’t seem to have a problem with Peckinpah, though…). Or at least, that was the party line in print. For The Cowboys, the point of contention apparently was the film’s moral, which many critics interpreted as “John Wayne, that fat old conservative dinosaur, turning young boys into murderous thugs.” Quite a few thought the movie repugnant because of its Old Testament “eye for an eye” attitude being forced on innocent, sweet-faced kids, turning them into hollow-eyed, remorseless killers.

RELATED | More reviews of Westerns

Of course, this view was highly hypocritical, because those same critics lauded sickeningly violent sequences in other Westerns—Westerns that fit, curiously enough, their politics more closely, such as Little Big Man and Soldier Blue. Violence in politically left-of-center films: good; violence in conservative Wayne flick: bad (the same thing goes on today, with liberal critics and Hollywood phonies who tweet about gun violence…before wetting themselves with glee over the latest Tarantino orgy-of-violence).

What’s humorous about that critical viewpoint today is that it’s largely based on a fundamental misreading of The Cowboys. The main message of the movie is that these young boys have learned valuable life lessons on the trail from the strong, righteous, and (largely missed by the critics) tolerant Wil Andersen. SPOILERS When he’s gunned down by a vicious, unremorseful, psychopathic killer, they understand precisely what needs to be done to him. There’s no question this message is the central intent of The Cowboys.

RELATED | More 1970s film reviews

As director Mark Rydell, an avowed liberal filmmaker asserted in an interview, The Cowboys was an exciting adventure where young boys “get to play cowboys and shoot the bad guys” (tellingly: he never really addressed the seeming contradiction of the movie’s message with his own political beliefs). What critics at the time missed is that this lesson of retributional justice wasn’t imparted to the boys or forced on them by Wayne. They learned it by themselves, despite Wayne’s best efforts to the contrary.

Throughout The Cowboys, Wil Andersen and Jedediah Nightlinger go out of their way to protect the boys from the harsher realities of adult life in the Old West. Noting the fact that he lost his own two boys (“They went bad on me”), Wil tries his best to be a caring, loving father figure to the boys. Naturally, he’s not always successful (what parent is?), and he has to be reminded when his judgement fails (Jedediah telling him he was too hard on Dan when the boy admitted to being afraid to stand night watch).

For the most part, however, Wayne worries about the boys, thinking that they may be rushing too fast towards adulthood (when he spies them enjoying their first drink). Jedediah shields the boys, as well, from the dangers of growing up too quickly (he asks the wagon load of prostitutes, led by Colleen Dewhurst, to move along because he knows he won’t be able to keep the older boys away).

Critically, when The Cowboys could have gone all wrong—when Wil discovers Asa tracking him and realizes that a fight is eminent—it’s Wil who demands the boys act like boys again. He knows they’ve already matured into men; he tells them so. But he also knows that if he breaks out their weapons (all the boys were packing iron when they first arrived; Will locked the guns up), some of the boys would invariably get killed in the firefight. It’s Will who wants the boys to stay out of the fight, SPOILER a decision that ultimately saves the boys and gets Wil killed. As well, once Wil’s dead, Jedediah fights the boys who tie him up, demanding that they not go after Asa. He wants no part of their action, until he realizes they’re going to go after Asa anyway, regardless of whether or not he helps them (sly, amused Roscoe Lee Browne has a delightfully natural rapport with gruff Wayne).

Quite correctly, screenwriters Irving Ravetch and Harriet Frank, Jr. allow the boys to develop their own sense of justice. The two male authority figures wanted them to stay boys, to stay safe. The boys, now men (regardless of their numerical age), finally understand how random and cruel life really is, and how sympathy and compassion should be reserved for those who deserve it, like Wil. And dispassionate justice, in the truest sense, should be meted out to the truly deserving, as well.

Some critics also complained that the violence was unrealistic (they forgot that the boys brought their own guns, and that in those days, young boys learned how to shoot and hunt early), but what was Rydell to do, have some of the boys die at the end? The point of the fable in The Cowboys is the death of Wil—the death of the father figure—and the passage of the boys into manhood. Boys dropping like flies in the final confrontation would have been a cynical, faux-realistic Peckinpah ending that would have made a mockery of what preceded it.

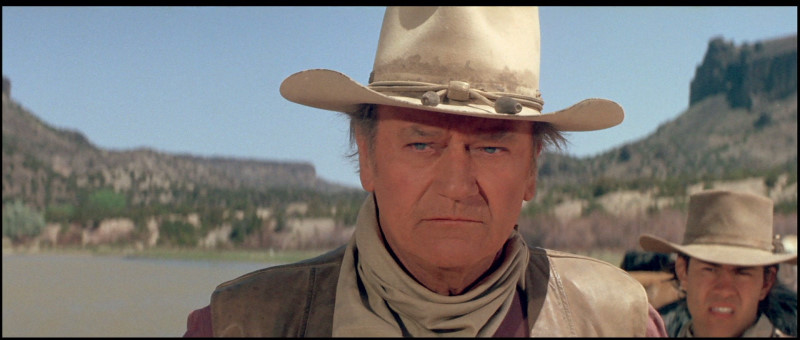

Wayne is particularly good here in The Cowboys. Looking alarmingly older and more ill than he did just three years prior in True Grit, and audibly short of breath, there’s a subsequent vulnerability to his imposing physical presence that transfers well to his characterization. There isn’t that mythic invulnerability to his performance; we don’t believe he can survive every dangerous encounter he comes upon. In fact, there’s almost a feeling of dread when he goes to fight Dern; we’re not sure he’s going to come through it alive. That’s a most unusual audience emotion in a John Wayne film.

Bruce Dern, who cornered the market on movie crazies in the 1960s and 1970s, does a neat trick of being totally over-the-top in his villainy here, but with no corresponding audience delight. He’s a vicious, amoral killer in The Cowboys, but the audience doesn’t applaud his outlandish energy. Dern, a most talented actor, truly pulls out the stops here (his physical assault of the young Dan, nearly drowning him in the river, is memorable—just watch the kid actor’s face; he’s really freaked out). Dern is certainly Wayne’s most believable bad guy (Dern often jokes that the role “ruined” his career, when in reality it probably cemented it…for better or worse).

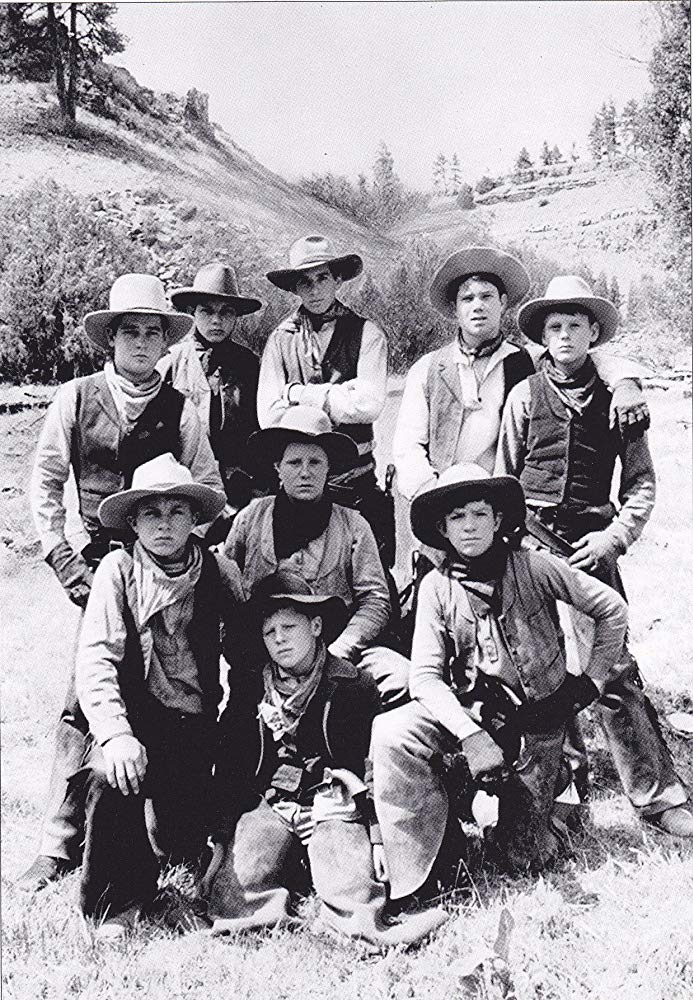

The boys, some of them familiar from other films (I would imagine Robert Carradine and A. Martinez went on to be the most recognizable to audiences), are uniformly fine. Director Rydell, a former actor, admirably keeps the boys acting like real boys; there isn’t a showy, actorly performance in the bunch. It’s really a testament to his directorial sensitivity that Rydell, a former street kid from Brooklyn, was able to helm such accomplished Americana period pieces like The Cowboys and 1969’s gentle, lovely The Reivers, with Steve McQueen (both share a story of a young boy(s) discovering the harsh realities of the adult world…but they couldn’t be further apart in tone).

PAUL MAVIS IS AN INTERNATIONALLY PUBLISHED MOVIE AND TELEVISION HISTORIAN, A MEMBER OF THE ONLINE FILM CRITICS SOCIETY, AND THE AUTHOR OF THE ESPIONAGE FILMOGRAPHY. Click to order.

I loved the message of an eye-for-an-eye, but did not care much for the film, though great to look at it. I could have done without the boys, which is the essence of the narrative, and who wants John Wayne to be murdered? I do not. Glad he had a hit, and for any anti-progressives, this should solidify your thinking, if required.

LikeLiked by 1 person