Please, sir…may I have some more filth?

By Paul Mavis

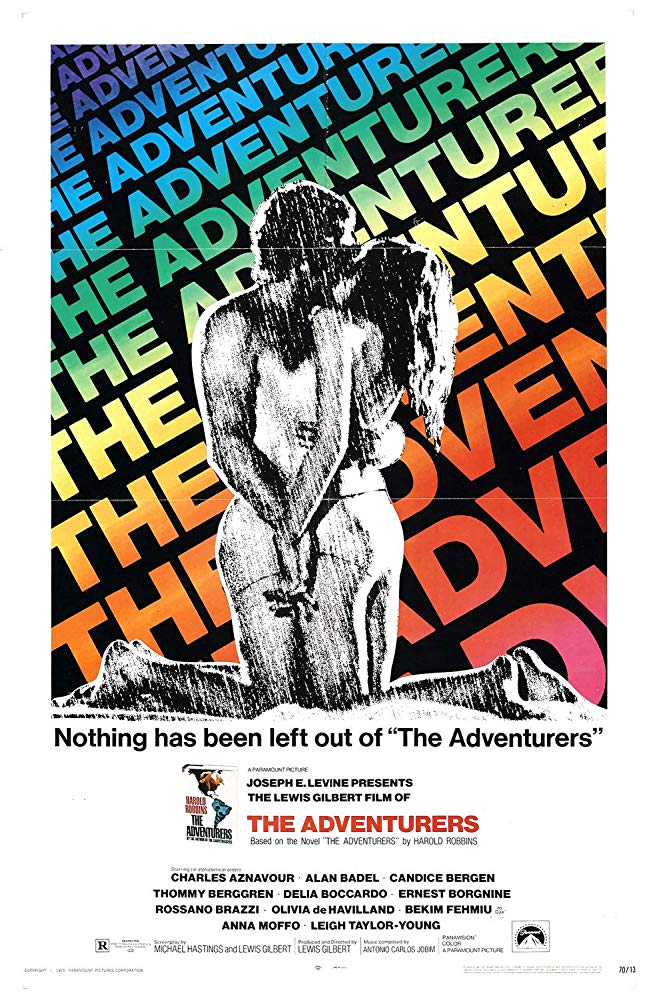

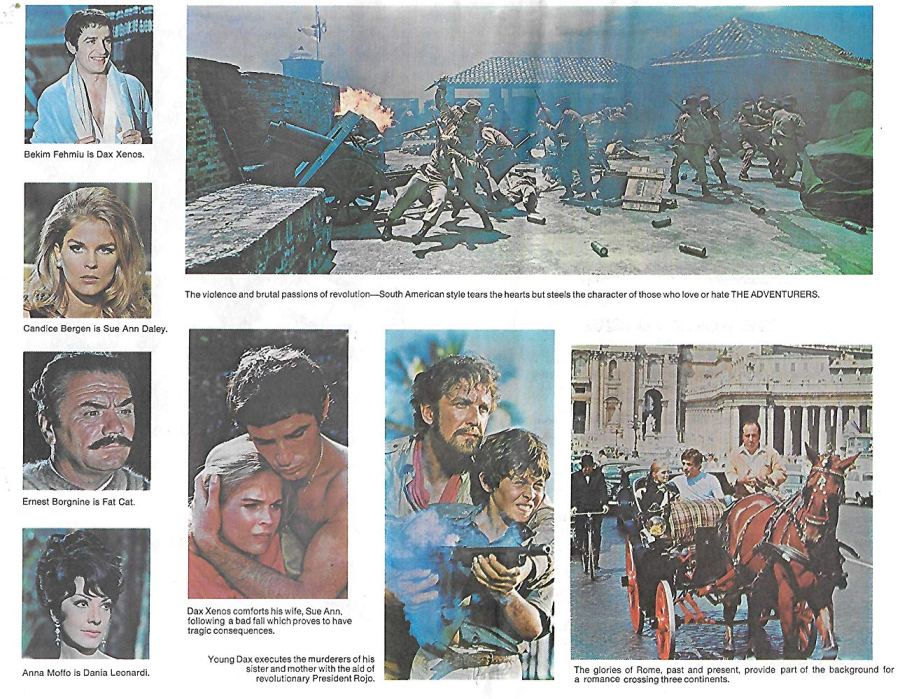

If Warner Bros.’ Archive Collection is going to re-release everything on Blu-ray…how about the deliciously rank and misguided The Adventurers, Paramount Pictures’ and Avco Embassy’s behemoth of a trashy political/sex/action melodrama from 1970, based on the best-selling potboiler from the master, Harold Robbins? Executive produced by crapmeister Joseph E. Levine, produced, co-written and directed by slummin’ it Lewis Gilbert, and starring an impossibly hilarious cast including Bekim Fehmiu, Ernest Borgnine, Candice Bergen, Fernando Rey, Alan Badel, Charles Aznavour, Delia Boccardo, Leigh Taylor-Young, John Ireland, Jorge Martinez De Hoyos, Christian Roberts, Thommy Berggren, Anna Moffo, Sydney Tafler, and Olivia de Havilland (um…excuse me?), The Adventurers is part faux-David Lean, part lurid comic book with funny accents and naked breasts—and all of it an irresistible, frequently maddening mess.

Click to order The Adventurers at Amazon.

Your purchase helps pay the bills at this website!

The Adventurers‘ reputation as a commercial disaster is only half right (it sold plenty of tickets…against a huge, unrecoverable budget), while a majority of critics yesterday and today continue to hold it up as an example of bad moviemaking at its worst (or best, if you’re so inclined…like me). Unfortunately, the only thing that The Adventurers gets wrong is that it isn’t nearly putrid enough, focusing too much time on murky messages about the moral corruption shared by banana republic dictators and Eurotrash jet setters, while skimping on what we really want to see: the depravity. Still…you’ll have a lot of fun watching this three hour extravaganza flip its wig trying to satisfy its two competing drives. I feel wonderfully dirty all over, just thinking about it again.

Cortuguay, South America, 1945. 10-year-old Diogenes Alejandro “Dax” Xenos (Loris Loddi), is playing with his dog when the pooch is shot by government troops, led by sadistic Colonel Gutierrez (Sydney Tafler). Running to the safety of his hacienda, Dax is horrified to see the soldiers follow, where they rape and kill his mother (Roberta Haynes), his 16-year-old sister, Teresa (Zienia Merton), and all of the servants. Dax escapes, and finds his father, attorney Jaime Xenos (Fernando Rey), riding with revolutionary general Rojo (Alan Badel) and his troops.

Returning to the hacienda, Rojo offers Jaime the chance to machine gun the murderers of his family, but he demurs—something the numb, vengeful Dax does not, as he holds the weapon, guided by Rojo’s hands, and blasts the offenders to pieces. Sent to Rojo’s stronghold with guide Fat Cat (Ernest Borgnine…wearing Ruth Roman’s wig), Dax meets Rojo’s young daughter, Amparo (Roberta Donatelli). History repeats itself when Rojo’s hacienda is brutally attacked by Gutierrez, with Dax and Amparo barely escaping with their lives (Fat Cat, separated from Dax, manages to flee, as well).

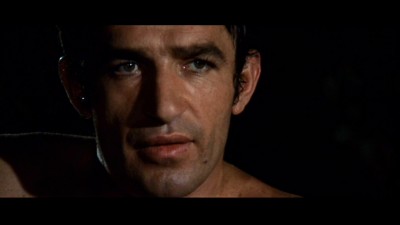

Enduring a horrendous trek to the capital city, Coratu, Dax and Ampara are seen by Fat Cat, and taken to their fathers, who are now the leaders of the successful revolution. Sent to Rome as Cortuguay’s ambassador, Jaime enrolls Dax into an exclusive boarding school, where Dax (Bekim Fehmiu) grows up to be a rich, handsome, hedonistic, dashing playboy, fond of fast cars, polo ponies, and beautiful women…and completely unconcerned with the trials and tribulations of his home country. True patriot Jaime Xenos, however, cannot ignore what has happened to his beloved Cortuguay: President Rojo, far from honoring his revolutionary promises to help his poor, oppressed “pipple,” has become a murderous dictator, spending fabulous sums of money on his sumptuous palace, while children starve in the road.

As Jaime heads back home to secretly meet with “El Condor” (Jorge Martinez De Hoyos), the leader of a new revolutionary opposition group to Rojo, Dax parties in Rome with his “jet set” friends Sergei Nikovitch (Thommy Berggren), a Russian diplomat’s son, and Robert de Coyne (Christian Roberts), the son of powerful international banker Baron de Coyne (Rossano Brazzi). Baron’s beautiful daughter Caroline (Delia Boccardo) beds Dax at a weekend orgy, but finds out that his horrific traumas as a child have left him bereft of any true feelings—particularly love. Tragedy follows Dax, though, when his father is blown up, forcing Dax to return to Cortuguay, where he accepts Rojo’s offer of being the new go-between for the rebels…and where he nails a grown-up Amparo (Leigh-Taylor Young).

Rojo double-crosses Dax, though, and slaughters the rebels, including El Condor, but blames Dax’s old nemesis, Gutierrez, for the massacre, whom Dax kills (are you following any of this?). With a death threat still ringing in Dax’s ears from El Condor’s vengeful son, Jose (Joal Carlo), Dax returns to Europe where, now penniless, he becomes a “paid escort” along with Sergei, under the pimping tutelage of slimy de Coyne gopher, Marcel Campion (Charles Aznavour); their proceeds are needed to start a fashion house for designer Sergei, while Dax needs the dough to return to Cortuguay as a true player in his nation’s politics.

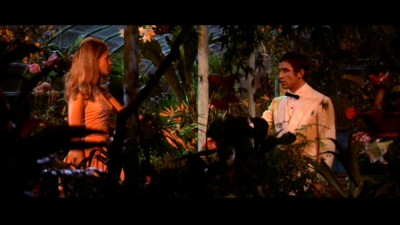

Developing a reputation as a handsome stud-for-hire, satisfying older, rich, lonely American tourists like Deborah Hadley (Olivia De Havilland), Dax sets his sights on marrying money—specifically, 20-year-old Sue Ann Daley (Candice Bergen), the richest virgin in the world, whom Dax eventually deflowers, marries, and impregnates in that order. A miscarriage (Has. To. Be. Seen. To. Be. Believed…) dooms their marriage, however, and soon Dax is back in Cortuguay with Fat Cat, working now with revolutionary “El Lobo” (Yorgo Voyagis), while discovering a shocking secret about Amparo.

RELATED | More 1970s film reviews

If you’re like me, you’re constantly cutting people out of your life for good who mean nothing to you because they failed one little arbitrary test that’s impossible to “pass,” anyway. Are you running out of ways to 86 them? Well…keep in mind The Adventurers—it’s an excellent litmus test for permanently excising from your sphere of consciousness anyone who isn’t a true “movie lover.”

A true “movie lover” embraces a seminal (sorry) occurrence like The Adventurers not in spite of its faults, but precisely because of them. To a “movie lover,” discovering The Adventurers for the first time carries the same weight as discovering in your attic that pesky final reel of The Magnificent Ambersons. To a true “movie lover,” the utter failure of The Adventurers signifies aesthetic enjoyment at a heightened, even spiritual level: its excesses are as endearing as its incompetencies are charming and amusing.

Beware the similar-appearing “ironic movie lover” chameleon, however, a poseur who watches a movie like The Adventurers to snort and feel self-important. There is no genuine, guileless love of swill in his or her heart—only ashes and furtive glances, looking for approval from anyone who got his “reference.” If you can find someone in your life who can watch The Adventurers with that same degree of rapture, hang on to them like grim death, for they are, along with you, part of The Anointed Ones—the Chosen People of the Great and Terrible Movie Gods. They are to be cultivated and cared for like the rarest and most delicate of alpine flora, just as the dusty, prickery weeds of the dreaded “film enthusiasts” who are “into cinema,” are to be unceremoniously yanked out by their roots, and, like pious recovering alcoholics, pro bowlers, and certified public accountants…to be avoided at all costs.

The movie adaptation of The Adventurers used to enjoy special status with that small group of movie lovers who cherished truly rotten flicks as much as they enjoyed “art” like Citizen Kane. Ironically, it’s been largely forgotten today…now that it’s readily available for anyone to see. Before cable, VHS, DVDs, and downloads, notorious bombs like The Adventurers were rarely shown on television, so by their scarcity they developed an almost mystical cache for lovers of cinematic excrement—a miasma of shared exclusivity among the faithful who were somehow able to get a glimpse at them—a private club that’s been destroyed by the distressingly plebeian democracy of today’s media saturation (perfect example: the minute they put the sublime Valley of the Dolls out on a special edition DVD, complete with a wretched commentary track and “helpful” extras, they killed that cult dead).

Equally forgotten today, I would imagine, is Harold Robbins, an author no critic or social commentator liked to talk about back during his heyday (the 60s and 70s) when Robbins was establishing himself as the best-selling fiction author of all time (well over 750 million books sold). Self-anointed critics—don’t you hate reviewers?—despised him because his books were on the coffee tables and bedside stands of hundreds of millions of homes and libraries all over the world…while their columns lined the bottom of parrot cages the next day. “Serious” authors dismissed him, with barely suppressed jealousy, as he jetted around to his three homes while they kept warm at night, wrapped up in their good press notices.

Of course the public didn’t care a whit about Robbins’ critical reputation (if anything, knowing he was despised by the toffs only made him more appealing); they only cared if he delivered the goods, and with novels like Never Love a Stranger, The Dream Merchants, A Stone for Danny Fisher, The Carpetbaggers, and The Betsy delivering truly prurient, scandalous sex scenes grafted onto poorly-written but quicksilver-plotted storylines, many of them thinly-disguised roman a clefs of real-life celebrities, Robbins, for good or bad, helped drag down American literature to its most base common denominator. And people all over the world loved him for it.

Some have called 1966’s The Adventurers Robbins’ last “good” novel, an ambitious tale mixing Third World politics and jet-setting playthings, not-so-thinly disguised from its real-life inspirations: international playboy Porfirio Rubirosa and his Dominican Republic dictator benefactor, Rafael Trujillo, with other composite celebs—like the Doris Duke/Barbara Hutton “Sue Ann Daley” creation—thrown in to keep the reader guessing (has anybody made a straight movie about the utterly fascinating Rubirosa? Because jesus do they need to…). Movie producer Joseph E. Levine optioned the book for Avco Embassy before it was even written (a cool million to Levine—that’s 1963 dollars)—a smart move he no doubt thought later, when his big-screen adaptation of Robbins’ The Carpetbaggers became the 4th biggest movie of 1964.

Considering the scope of the original novel (Robbins originally envisioned it as a hundred-hour television series at CBS), Levine went for broke, giving The Adventurers a massive budget in line with the best David Lean epics (one report had it at $18 million—a huge sum back in 1968-1969), with proven heavyweights behind the camera to gussy-up the tawdry material. British director and screenwriter Lewis Gilbert, hot off the international one-two punch successes of Michael Caine’s Alfie and the biggest Bond to that date, You Only Live Twice, was brought in for “class,” as well as for his ability to handle a multi-million dollar globe-hopping production.

Respected British playwright, screen-writer, and novelist Michael Gerald Hastings was hired to work on the script, as well, while the absolutely impeccable tech crew was indicative of the kind of serious perfume that was getting thrown onto The Adventurers turd to make it smell nice: Claude Renoir (A Day in the Country, The River, Barbarella) on the Panavision camera; David Lean alumnus Anne V. Coates (Lawrence of Arabia) editing; Tony Masters (Lawrence of Arabia, 2001: A Space Odyssey) designing the production, and bossa nova god, Antonio Carlos Jobim (Garota de Ipanema [The Girl from Ipanema]), on the soundtrack. Only with the casting can one detect, perhaps, a desire to save some money, with the biggest movie star names here (Oscar winners Ernest Borgnine, Olivia De Havilland) belonging to the supporting cast (I guarantee they first unsuccessfully pitched the Dax and Sue Ann roles to every Hollywood A-lister out there, before they settled for an “international” cast).

One would assume, considering the “Intermission” card that crops up after Sue Ann loses her baby, and the fact that some 70mm/stereo blow-ups were reportedly made for the bigger city venues, that Levine originally intended a “road show” platform for The Adventurers (whether this panned out nationally or not, I couldn’t find any solid information). When released in March, 1970, most major critics had a field day savaging The Adventurers. Ticket sales, no doubt stirred by curious fans of the author, were brisk (if it returned rentals of about $8 million, as reported, it probably did almost double that in gross ticket sales)…but not brisk enough to offset the huge budget and Levine’s customary expensive ballyhoo promoting the movie.

Considering the time period (1970) when Hollywood itself was seen by new critics and some younger audiences as an aging, cliched, “out of it” Establishment factory of worn-out dreams, it’s not surprising that big, bloated The Adventurers was pilloried by the press when released (New York critics first saw a 205-minute version, which was quickly edited down to 177). Robbins was already a convenient punching bag, so to see Paramount and Avco Embassy drop almost 20 million bucks on one of his rude, crude stories was too good to be true for the snots who reviewed back then.

“Big” itself was suspect during this anti-establishment period, with lush, expensive, old-fashioned, older-skewing properties like Airport, Paint Your Wagon, Ryan’s Daughter, and Hello, Dolly raising the ire of critics who raved over non-traditional hits like el cheapo Easy Rider. The fact that an overwrought meller filled with cheap sex and violence like The Adventurers dared to hit on political themes that the critics thought were better served in foreign imports like Z, only stoked the critical fires, while The Adventurers‘ ultimate message that Third World revolution is essentially a revolving door-joke that solves nothing for the people—a surprisingly grim, unrelentingly downbeat warning embodied in Dax’s, “Pillage. Rape. Destruction. Death. It’s always the same,”—further infuriated all the Lefties that infested the “New Film Criticism” at the time.

This incompatible three-way between a seemingly tasteful, opulent “big event” Hollywood epic, a crude, cheap exploitation meller full of sex, and a politically aware message “film,” is precisely what simultaneously sinks and saves The Adventurers: its tone, its focus, its purpose…they’re all over the place…and thank god for that. If The Adventurers commits any serious aesthetic crime—on all three fronts above—it’s that it isn’t nearly explicit enough.

The much talked-about opening sequence with Dax and the massacre actually indicates something quite radical: a David Lean epic that has big, hairy balls. Showing Dax playing with his dog in languid slow motion, Gilbert then shock cuts to the dog getting blown back out of the boy’s hands—so much for “a boy and his dog” sentiments—before the director wallows even deeper into depravity, illustrating a still-shocking rape and murder scene complete with nudity and slasher-like gore, as he keeps cutting back to young Dax, eyes wide, taking it all in (to the critics who decry this scene as repulsive: it’s meant to be. These things happen every day in all those revolutions in all those countries the media loves). Shot with the high gloss of Doctor Zhivago, Gilbert doesn’t pull the ameliorating trick Lean foisted on the viewer in that movie by focusing on Omar Sharif’s reactions to an off-camera slaughter happening below in the streets. Gilbert shows us exactly how sickening such mayhem is, without pulling the camera away.

As the topper, the screenplay then introduces a potentially rich dramatic vein of Greek tragedy proportions, as young Dax is pulled between his idealistic-but-pacifist father, and his amoral, killer father-figure Rojo, who lets Dax shoot his mother’s and sister’s murders not once, but twice, just to make sure they’re dead (only an English ham bone like Badel could re-interpret a South American strongman dictator as a bitchy queen haberdasher who disapproves of your cuff length).

And then…a serious expansion of that intriguing storyline is all but abandoned as we move from one huge set piece or sex scene to another, while proclamations about love, and feelings, the emptiness of money, and the dignity of “the pipple,” are delivered with the solemnity of a bad church sermon. It’s nutty, but after that arresting opening sequence, we can’t for the life of us figure out where Gilbert is going here—sexploitation meller, or faux-“serious” epic—as the movie ping-pongs crazily back and forth between the two impulses, satisfying neither, while any meaningful intent with the politics is left behind.

I’ve read and heard conflicting information as to whether this 177-minute version of The Adventurers is the true “R” rated movie that first premiered in 1970. I can guess that something has been cut here (for starters: an “Intermission” title card, but no corresponding “Entr’acte” included?), while I suspect that Gilbert shot a lot more nudity and sex than shows up here (Leigh Taylor-Young didn’t show any compunction about baring it all for that same year’s The Big Bounce, but she’s positively demure here). Regardless of what version this is, The Adventurers is, in a word, “tame.” I don’t care how daring it was for 1969-1970, you could see more “action” in an AIP drive-in programmer at that time than you see in The Adventurers.

Just as an example, we don’t get to see any of Robert’s Roman orgy in The Adventurers: we get carefully-composed, PG-rated shots of nude, sleeping actors after said orgy. Gilbert isn’t afraid to show the sexual sadism of the marauding government troops in the opening sequence, but he goes all romantic and chaste with the Eurotrash set…when their exploits could have and should have been equally base and tasteless (we hope). Bekim Fehmiu and Delia Boccardo are naked by the pool (in the famous image slightly altered for the one-sheet poster), but Gilbert can’t decide if it’s serious (those cool shots of the sculptures “watching” the couple) or laughable (the camera hilariously zooming in and out on Boccardo’s face to mimic Fehmiu’s pelvic thrusting).

We’re given a very strange superimposition of Fehmiu visualizing his sister’s rape—a memory that makes him bite Boccardo’s shoulder in…what? Lust? Anger? We’re never told, with the movie apparently uncomfortable exploring this psycho-sexual connection (contrary to most reviewers, I rather liked Fehmiu’s performance. A star in Europe at the time, he has a mashed-up, Belmondo-esque quality that works here). Bergen’s infamous “deflowering” in the greenhouse is even more bizarrely virtuous, as Gilbert shows us hothouse flowers and exploding fireworks (yep, it’s that subtle), and never-nude Bergen is only allowed a tight close-up of her orgasmic pleasure. Watching this howler of a scene, you seriously have to wonder if human dress form Bergen ever even had sex before this was shot, so incompetent is her pallid, robotic attempt at conveying overwhelming gratitude for her release (the sight of Charlie McCarthy’s sister simulating an orgasm should be conjured up by every guy out there tired of using math problems and baseball scores…).

It’s a cheap, easy generalization, but perhaps what The Adventurers needed, if we wanted the movie to aesthetically “succeed” (which we bad movie lovers most decidedly do not) was not a laid-back British helmer looking to make something “respectable” out of eminently disrespectful material, but rather a crude, lowbrow American director looking to score points in the tits and ass department. The more “serious” The Adventurers tries to be, the more laughably phony it is, while all we want it to do is really let loose…while all it keeps doing is grabbing the sheets to cover up.

Once that promising opening sequence is over, and the sex doesn’t appear, The Adventurers is “saved” by rapidly piling up boners (sorry) in atrocious taste, with the whole enterprise sagging deliciously under its ungodly three hour weight. For some unknown reason, Gilbert immediately (and completely nonsensically) undercuts that horrendous opening scene by having Dax unknowingly making a joke about raping and killing Amparo, cued deliberately to make the audience laugh, for god’s sake, as we wonder how much further The Adventurers is going to go off the rails. A seemingly unending series of scenes come and go, with almost no context—why is Sergei’s diplomat father now a doorman? How does Dax immediately seduce the grown Amparo? Where the hell does “true love” Caroline disappear to in the middle of the movie? Why does stick thin Bergen keep insisting she’s fat?—as the movie turns into a kaleidoscope of mistimed, ill-judged, and frustratingly promising scenes that just end, bizarrely, without adequate set-ups and pay-offs.

It’s a toss-up as to the movie’s most egregious mistake—Aznavour’s torture sex chamber (we don’t know why it’s there, we don’t know who’s been in it, we don’t know why we’re being shown it, and worst of all…we’re not allowed to see it in action), or Bergen’s slow-motion miscarriage via seaside swing (when she first starts swinging in slow motion on it, one begins to see how surreally—how magically—The Adventurers is completely and totally f*cked). Gilbert tries to wind the whole thing down with about another hour of battle footage and crowd scenes, impressive in their scope…and completely useless by this point in creating any meaningful statement. As the credits roll, you don’t care that Robbins’ and Gilbert’s point is valid—nothing changes in these countries; the poor are victims under any regime—all you know is you’ve seen something that is truly rare: a movie of cosmic, monumental ineptitude.

And you loved it.

PAUL MAVIS IS AN INTERNATIONALLY PUBLISHED MOVIE AND TELEVISION HISTORIAN, A MEMBER OF THE ONLINE FILM CRITICS SOCIETY, AND THE AUTHOR OF THE ESPIONAGE FILMOGRAPHY. Click to order.

[…] to work up that kind of emotional involvement with an actress like Bergen (I beat her up enough in The Adventurers: let her critical reputation rest in peace). For the story to be believable, however, we have to […]

LikeLike