It’s Halloween, so…you ever been in a psycho-sexual fugue state? It’s fun.

By Paul Mavis

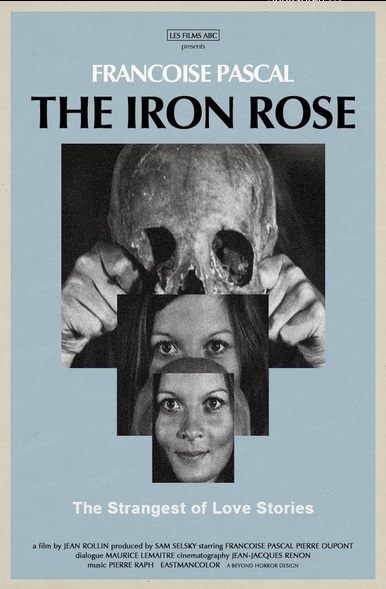

Maddening only if you fight it, cult director Jean Rollin’s The Iron Rose (La Rose de Fer; released here in the States as The Crystal Rose), is a beautifully languid fantastique from 1973, one that will entrance romantics and daydreamers and various other headcases with a gothic bent…and no doubt disappoint newer horror fans expecting lots of skin and gore. Starring the gorgeous Francoise Pascal and Hugues Quester, The Iron Rose‘s insistence on atmosphere and visual poetry over any semblance of plot, concrete explanations, blood or nudity, keeps it timeless. It isn’t meant to be figured out. It’s meant to be experienced much like hearing a poem…if that poem dealt with death and sex, read by campfire in a spooky dark forest.

Click to order The Iron Rose on Blu-ray or DVD:

(Paid link. As an Amazon Associate, the website owner earns from qualifying purchases.)

After a walk on a foggy, dreary beach, where a beautiful girl (Francoise Pascal) finds a rose made of iron (does this really happen first in the film, or is this a flashforward? As with almost everything in The Iron Rose, there’s no real answer). She walks through a seemingly deserted town, eventually finding herself at a wedding reception. There, a handsome young man stands up and asks permission to give a poem…a poem about a couple longing for death (some wedding gift). Outside, the young man meets up with the girl, and admits he gave the poem as a way of meeting her. They agree to take a bike ride the next day.

After frolicking at their meeting place (a foggy deserted railway station), they ride into town, where they stop for lunch outside a massive, overgrown cemetery. She doesn’t want to enter, but he cajoles her into going inside, and they start to explore the impressively spooky enclave. Settling in for a snack, the man knocks over a cross, and they see an old woman, dressed in black, walking around the grounds with flowers.

They continue to explore the grounds, and the girl and boy discuss souls and death. They come across an underground crypt, covered with heavy metal, sealed doors, while a strange, berobed man (Rollin in a cameo) watches them intently. A clown in full makeup puts flowers on a grave. The young man goes into the crypt, while she begs him not to—but she eventually follows, and they make love.

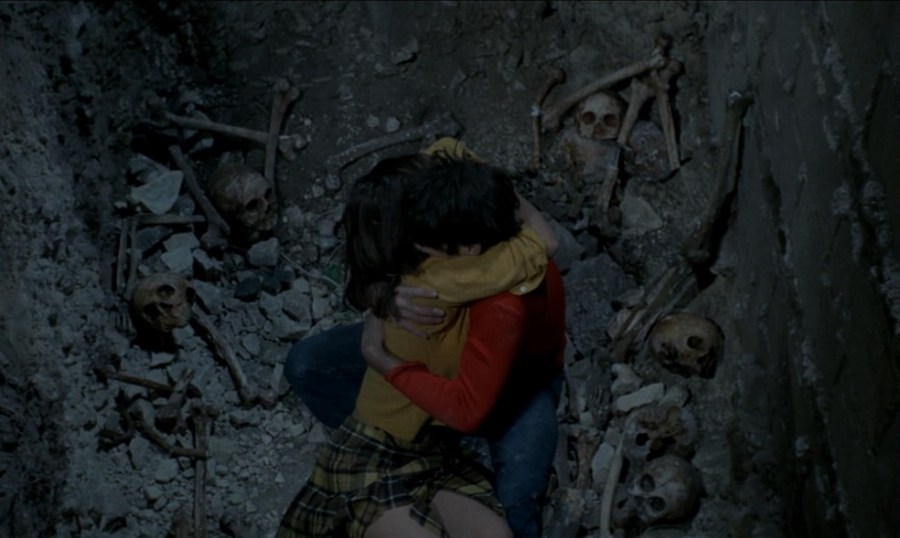

When they’re finished, they look up to discover it’s night. Worried, but still calm, they make their way out of the crypt, and search for a way out. But no matter what direction they take, they either wind up back where they started, or find endless more sections of the graveyard. The girl begins to panic, and the boy attacks her, which eventually leads to another lovemaking session in an ancient exposed burial pit, atop the bones and skulls of a mass grave. However, it soon becomes apparent that time spent in the graveyard has significantly changed the girl….

Those looking for explanations in The Iron Rose are on a fruitless quest. Rollin himself has stated that he wanted to make a movie as close to a spontaneously made-up campfire story as possible, with a sense of impenetrable dread and eroticism permeating the largely silent, diffused narrative (it sure helps when a director emphatically states what their movie is about). As well, the primary thematic element of the fantastique genre is the inexplicable appearance of supernatural elements that the protagonists cannot and will not accept or understand.

RELATED | More horror movie reviews

The Iron Rose isn’t really about anything, other than creating a visual poem that intrigues and mystifies the viewer. Of course, you can employ “Film Criticism 101” theories (blech) as to what Rollin is really doing; that’s always fun to do. There’s certainly enough overripe filmic semiology and seemingly portentous symbolism to spur on any “Criterion Collection forum member” “cineaste” (douchebag) looking to bore his after-dinner guests (the girl’s gradual journey from unwilling visitor at the cemetery to her uncontrollable urge to make love in the grave pit, to her desire to join her lover in the sealed pit for eternity…all linked by the obviously symbolic iron rose ornament, is a start). But by Rollin’s own admission, much of what he includes in The Iron Rose is put there for visual and emotional impact—and not for logical examination.

That being said, The Iron Rose shouldn’t be approached in any manner as a traditional horror film from the 1970s—or at least the kinds of horror films that usually played here or abroad. That isn’t to say that The Iron Rose was even well received in Rollin’s native France: it was a financial and critical disaster when first released (it didn’t help that sensation Last Tango in Paris opened the very same night in Paris). Traditional “horror” film elements included in The Iron Rose—the young man screaming to be let out of the crypt, the young girl holding up a skull to cover her face (a marvelously creepy image)—are few and far between.

And as for nudity, it does show up, once, with the sensual, lovely Pascal nude on the beach during a flashback (or is it a flashforward?). But that’s certainly not the point of The Iron Rose, either. Rollin had done soft-core porn before The Iron Rose, so he obviously wouldn’t have been adverse to filming overt sex scenes. When the couple make love here, it’s discreet enough for a PG-rated film.

What Rollin is trying to achieve is a sustained atmosphere of suppressed, macabre eroticism; there’s no need to be explicit in either the horror or sex elements to get across his musings on death, sex, the soul, and simple, primal terror of being lost in the dark. Critical to the success of The Iron Rose is the simply amazing location used for the cemetery where spoilers alert our protagonists end their lives (Amiens’ famed Madeleine Cemetery).

The cemetery pictured here is unlike any I’ve seen here in the States. A massive, decaying ruin, with crumbling monuments overgrown with weeds and covered with autumnal leaves, the grounds are crammed with huge, overarching trees that give the place a primeval feel, as if this was the first cemetery ever conceived. And Rollin, with his cinematographer Jean-Jacques Renon, do a remarkable job of conveying a mossy, decomposing deathscape, shrouded in fog and utter, frightening darkness (a kind of true darkness you never see in most movies, where the “night times” always seem too highly lit), that delivers the appropriate shudders (aided as well, by the evocative Pierre Raph score).

RELATED | More 1970s film reviews

Key also is the performance of Francoise Pascal, who has a perfect enigmatic allure—as well as a perfect, highly desirable sexual presence—that believably conveys to us the dichotomy of her emotions. Believable as reluctant to enter the cemetery, we’re equally drawn to her decision to make love to the boy not only in the crypt, but later in the open skull-and-bones pit. Why does she do it? Who knows?

But Pascal’s highly charged sensuality, nicely shaded by a tentative, hesitant fearfulness (epitomized by Rollins’ smart move of costuming her in an innocent—and tempting—schoolgirlish pleated tweed skirt) has impact enough to convince us that something, however inexplicable, is driving her on (…or maybe nothing is driving her on; she’s just walking through a nightmare, as we do in our own).

Quester is less successful with his role; it’s unclear as to whether he should be viewed as some kind of tempter, initiating her into crossing forbidden borders of religion and sex, or as flat-out scared lover who’s terrified of his gradually flipping-out pick-up. Whether that ambiguity is Rollin’s intention, or the fact that Quester was reportedly at odds with his director from day one (he even had his name changed in the credits), is unclear. But again, that abstruseness is part and parcel of Rollin’s wonderfully evocative design for The Iron Rose. Don’t fight it; don’t try and noodle it out—just experience it, and float along on director Jean Rollin’s marvelously sensual tone poem of eroticism and death.

Read more of Paul’s movie reviews here. Read Paul’s TV reviews at our sister website, Drunk TV.