Another summer of fun, right? Hot dogs, baseball games, grandma’s old-fashioned cracker crumb cake, lazing on the front porch at dusk, watching the fireflies, waiting for the next government-sanctioned assassination attempt…it’s been a real scorcher. I’ll tell you what’s not hot—Al Pacino’s Bobby Deerfield, the ludicrous 1977 Sydney Pollack attempt to marry Formula One racing with a made-for-TV “disease of the week” romance. Hoo boy! It’d knock a crow off a shit wagon in July!

By Paul Mavis

Now don’t stop reading. This long [not] awaited Blu-ray release from Mill Creek Entertainment is doubled up with a far superior Pollack effort—the marvelously strange, dreamy war actioner, Castle Keep, starring Burt Lancaster—and that outing is well worth picking up this Blu disc (we’ll review Castle Keep in a few weeks—it’s not a summer; it’s an autumn). And besides, Bobby Deerfield is so thoroughly misguided, so atrociously scripted and embarrassingly performed, that it’s certainly worth a look if you’re in the mood to look down on a bunch of phony Hollywood A-holes who tried to make “art,” and wound up with “caca.”

Click to order Director Spotlight: Sydney Pollack Bobby Deerfield/Castle Keep on Blu-ray:

(Paid link. As an Amazon Associate, the website owner earns from qualifying purchases.)

The European Formula One racing circuit, 1977, where bored, handsome drivers race around and around in endless circles, inbetween smoking constantly, making unenthusiastic love to beautiful, bored women, and staring off into space for hours at a time, their hollow, empty eyes indicating either great sorrow, or a brain tumor. American driver Bobby Deerfield (Al Pacino), from top-of-the-food-chain Newark, N.J., moves somnambulately through dull races, dull conversations with his colorless main squeeze, Lydia (Anny Duperey), and photoshoots and TV commercials hawking crap he doesn’t care about (Seiko watches. Really?).

He has family back in the States, including his tight, anxious, polyester sports coat-wearing brother, Leonard (the late, great Walter McGinn, totally wasted here). But all Leonard wants to do is hassle Bobby, telling him he has obligations coming up because their mother is getting older, and there’s some property to take care of, and a whole bunch of long-simmering sibling baggage Bobby frankly doesn’t want to deal with now—or ever (we know this because Bobby hides behind sunglasses all the time…).

Even worse, a fellow driver, Karl Holtzmann (Stephan Meldegg), inexplicably fails to make a turn during a race, crashing and becoming paralyzed, and now Bobby’s truly spooked. He doesn’t want to drive anymore until he finds out what went wrong. Was it a dog running towards the course? A bunny rabbit? Or was it Paul Newman, who originally owned beloved pet project Bobby Deerfield, and who was freaking out when he saw how much Pollack and Pacino were f*cking it up? It’s hard to say.

But now, Bobby wants to take some time off and get his head together. Which is impossible because he doesn’t know where his head is at in the first place, you know? You see: his life is dead. He doesn’t know how to love.

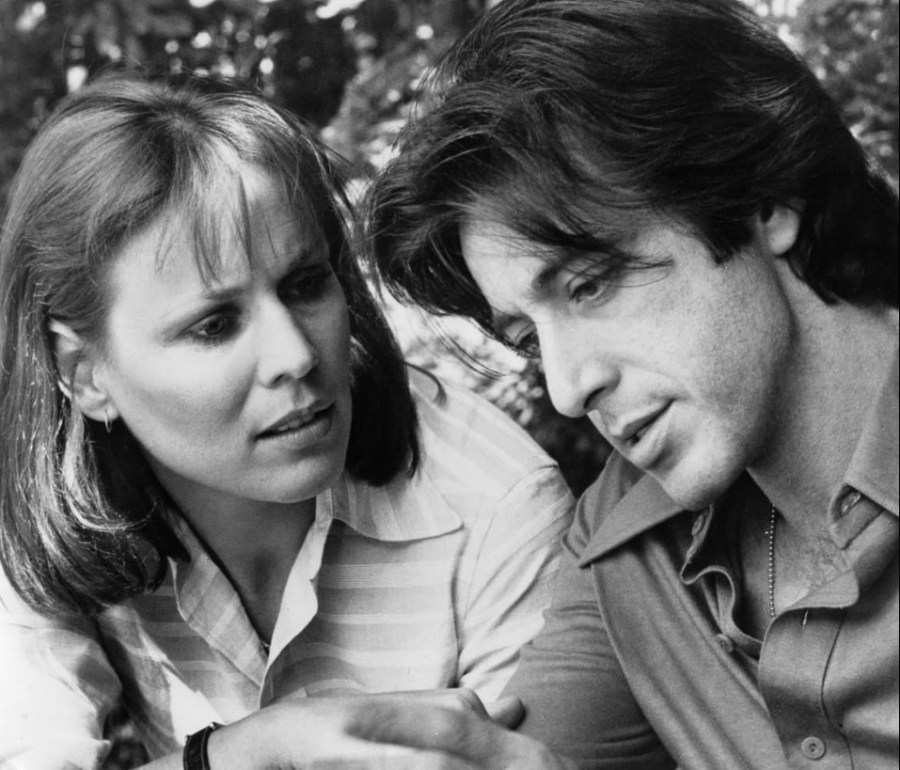

Enter kooky dying Italian-with-a German accent jet setter, Lillian Morelli (Marthe Keller), who’s staying at the exclusive sanitarium where Karl is being warehoused. She’s obnoxious and rude (in a Hollywood movie, that means we’re supposed to find her adorable and irresistible), and she talks a mile-a-minute stream of consciousness bullshit that would make anyone other than Al Pacino want to run her over with a car, Formula One or not, in five minutes flat. She constantly baits and taunts Bobby, calling him “boring” I don’t know how many times, urging him to chase hot air balloons and scream in railway tunnels, and all those other charming things young lovers do when they’re first getting to know each other.

And naturally, Bobby is smitten. Her abuse has stirred something in him (if a guy acted this way towards a woman in a movie, you’d all be saying how abusive he was, how manipulative he was, what a psycho he was, so shut up). He may be the last person in the movie to figure out she’s dying, but he’s going to get there, with a lot of effort, a lot of staring off into the void, before something in his addle-pated head “clicks” and he realizes…well, we’ll talk about that, won’t we?

I saw Bobby Deerfield in 1978, on my beloved Showtime premium cable box (sometimes, when the little switch didn’t work—from overuse—we’d have to put lock-vise pliers on it), and I’m pretty sure I didn’t do my usual, “I’ll watch this movie ten times because it’s a novelty to see any uncut big-screen movie on TV,” bit. Bobby Deerfield didn’t land with me back in 1978, and it sure as hell doesn’t work today (although I now see some people referring to it being a “cult” movie…which is total bullshit).

I remember when Bobby Deerfield came out, and the critical perception was Pacino, an intense, unpredictable actor known for carefully choosing uncompromising material like Serpico, Scarecrow, and Dog Day Afternoon, had “sold out,” making what was essentially an expensive, glossy vanity project that was retreading ground already covered by countless other movies (certainly blockbuster Love Story would have been in the producers’ rear view mirror in 1977) and even made-for-TV quickies. I guess it made money (more in Europe than here in the States), but it did no one’s reputation any favors as it quickly dropped off the public’s radar.

However, calling Bobby Deerfield a “vanity project” is quite frankly an insult to that time-honored, self-indulgent perk so many Hollywood stars have ordered up when they’re feeling all fat and sassy. A vanity project is supposed to make the star look good (fabulous clothes, stunning locales). It’s supposed to give them big, melodramatic scenes to crash around in, to give the Academy fodder for a Best Actor or Actress nomination. And it’s supposed to the give the audience some vulgar thrills for their hard-earned bucks.

RELATED | More 1970s film reviews

Bobby Deerfield does none of that. At the time, director Sydney Pollack stated he deliberately set out to make a movie that went against the conventions of the two genres he was melding into Bobby Deerfield. No big action scenes. No big glossy set-pieces allowing for beautiful clothes or picturesque framing. And no big handkerchief-wringing scenes to impress Oscar voters (even the “gloss” is botched, with surprisingly muddy cinematography and yet another abysmal light jazz soundtrack from Dave Grusin).

So, for the sake of “making something important,” Bobby Deerfield audiences were cheated out of the pleasures of both genres’ expectations. It’s no racing movie (there’s only about five minutes total running time of cars and drivers, shot in the most banal, unexciting manner imaginable), and it’s not even a “dying romance” movie, either (we see her stumble into one china shop display table. Big deal). At the time, Pollack offered he didn’t want to make a movie about a woman dying, but rather a movie about a man’s life being saved by a woman dying.

Fine. Great…but you still have to show the woman dying so the audience can see the man’s transformation and to see how her triumph-over-suffering gives him new insight. Audiences expect that from this kind of movie. They want to triumph over death, too, while they safely sit in the dark movie theater. Enjoying other people’s suffering is what melodrama is all about, particularly if the victims are rich and/or beautiful and they have everything to live for…but can’t. You deny the audience that vicarious pleasure, and they’re going to reject your multi-million dollar Hollywood product, masquerading so unconvincingly here as a European art house flick.

Pollack, a facile, not particularly deep director known for delivering financially successful entertainments like Jeremiah Johnson, The Way We Were, Three Days of the Condor, and later Tootsie, must have decided he needed to deliver up some “art” this time around with Bobby Deerfield. Working with a top-notch scripter like Alvin Sargent might have resulted in an assured mix of the polished and the popular, but only if Sargent had delivered an A-game script, which he most decidedly did not here (to be fair, according to several sources, the script was mangled on a daily basis, due to Pacino’s and Pollack’s squabbling).

You know you’re in trouble with Bobby Deerfield right from the waving of the green flag: that phony, dead-end opening sequence, a nightmare Pacino is having about the track. Mumbling something about needing a “key” to start his car that needs no key (yep…it’s that kind of movie), Pacino walks the track while the Foley artist sets the sound effect, “Pacino’s footsteps,” to “Hulk walking,” (his feet sound like they’re made of concrete). He wakes up in terror (we, however, feel nothing), before Pacino tries out a bunch of actor-y bits like checking his pulse (why?) and trying to light his Virginia Slim under the sink faucet (again: why?). None of it works, and it’s only the first scene!

Not to be outdone with this opener, Pollack and Sargent screw up almost every subsequent scene in Bobby Deerfield. It’s not like their overall vision for the movie was strong or original to begin with, but couldn’t they at least have tried to entertain us, if they couldn’t enlighten us? Clinkers abound. At times, the curiously self-destructive editing elicits laughs (one minute Pacino is yelling at his mechanics to not give him that whole “driver error” business to explain Karl’s crash…right before the scene shifts to Pacino stating Karl was distracted by a rabbit…which would be the very definition of driver error, genius), while the dialogue is maddeningly puerile.

A particular stand-out is Pacino’s penchant for repeating everyone’s lines (there’s a drinking game for you); Keller’s character even calls him out on it, telling him it’s “boring,” (did the screenwriter actually writing this self-criticism, or did Keller ad-lib it?). It becomes hysterical after awhile, trying to guess which line thrown at him will earn a repeat (I love when his girlfriend tells him the simplest thing—”Your brother is on the phone”—to which a put-out, uncomprehending Pacino parrots back, “My brother? What do you mean, ‘My brother’?” Bobby Deerfield could have redeemed itself, in entirety, if they had only allowed her to answer what everyone in the theater was thinking, “It means your brother’s on the phone, you moron.”

Bobby Deerfield has so many inane, dead-end, dead-head conversations like that, the viewer can’t help but become not just disinterested in the characters, but active agents in wishing for their immediate demise…just to shut them the hell up. Table tennis back-and-forth discussions about death, destiny, magic (yes, magic), and god, don’t remind us of Aristotle and Descartes here, but rather Abbott & Costello, with Keller manically blathering on about hospital bills, feminine men, and “homos,” eliciting the now-classic Pacino response, “We build them there [in Newark]. We have homo factories.”

After insisting not once but twice that a car is an extension of a man’s penis, she politely asks Pacino, “Would you care to scream with me?” in a train tunnel, with the only possible audience response being, “Can she die already?”

Like all artistic posers with intellectual inferiority complexes (Pollack once said he didn’t know anything about movie history, and that he saw very few movies growing up), Pollack here has let himself be seduced into thinking this shit is actually meaningful, when it’s merely pretentiously vague, and more to the point, annoying as hell. He thinks if everything in the movie is slowed down to a crawl, including the performances and the pacing, if everyone stares off into the distance, contemplating…what, I don’t know (and neither does he), that that equals intellectual and emotional “deepness.” It’s laughable. It’s like a high school senior suddenly discovering that phony Camus. It’s embarrassing (Pollack’s idea of movie symbolism is having a sleeping Keller wake up to Al’s revving, “alive” engine, and then see a coffin carried out of her sanitarium).

Bobby Deerfield‘s most memorable scene—the lyrically pretty hot air balloon rally—might have worked in another movie, with Pacino shouting questions at Keller as she serenely lifts off into the air. But here it fails as metaphor or symbolism or allegory or whateverthehell, because we simply don’t care about these characters (there is one genuinely fine scene in the movie, a very simple, short moment where Italian Aurora Maris—I have no idea if she’s an actual actress, but she should have been—helps Pacino translate a note from Keller. It’s the most real, natural, charming moment in the movie).

And we don’t care about these characters not just because of the inept screenplay—the performances are just as dire. On a physical level alone, Pacino is miscast. I’m sorry, but I don’t believe Pacino has the upper body strength and stamina to pilot a riding lawn mower, let alone a powerful Formula One racing car. That aside, he embodies almost none of the qualities we associate with athletes in that particular sport (at one point, he blankly states he doesn’t think about danger, death, or speed when racing…okay, what the hell else is there to racing?).

In fact, Pacino doesn’t seem to embody too many qualities we associate with existing as an actual human being, beside walking, talking, and blinking. He’s a neurasthenic robot here in Bobby Deerfield, clearly at odds with a meaningless character that doesn’t speak to him (Pacino later said Pollack didn’t get the character at all). The pregnant pauses and the constant silent staring become laughable after the first five or ten scenes. And it never stops. He never achieves lift-off.

When Pacino does try to convince us he has actual human emotions, he utterly fails. When he’s told Keller is dying, the camera stays on him while he looks like that gas station burrito is repeating on him (my wife, who uncritically accepts any movie in the “dying romance” subgenre, cried out, “He’s gonna barf!” before collapsing in giggles).

The absolute nadir of his career (and no, it wasn’t Cruising, which looks better and better every year, and no, don’t you dare say, “Dunkachino”), the lowest point he has ever sunk onscreen, comes here when he does his Mae West imitation—yes…Mae West—for Keller. Is he indeed actually imitating Mae West, or simply “coming out” to then-real life girlfriend Keller (by the look on her genuinely troubled face, I’d say the latter). Pacino looks so mortified, so internally frozen and paralyzed with embarrassment, it’s a wonder he allowed Pollack to film this scene (so what if Pollack was also the producer. Pacino was the A-list star: one phone call to Columbia and Gordon Douglas would have been on the first plane to Paris…and Bobby Deerfield would have been a hellava lot more entertaining, I would imagine).

As for Marthe Keller, I’m still trying to figure out 1976-78. In those two years, she had four incredibly high-profile Hollywood releases: Marathon Man, Black Sunday, Bobby Deerfield, and Billy Wilder’s Fedora. How this happened for this relative nobody (at least in terms of U.S. audience recognition) is still beyond me. Needless to say, her subsequent resume, at least in terms of Hollywood projects, indicates how well her introduction went over with Hollywood suits and American ticket buyers: she basically disappeared.

And it’s not hard to see why here in Bobby Deerfield. Simply put: she’s totally wrong for this part. For her character to work at all, we have to find, in the end, her terror-induced patter and flighty behavior endearing (much like we did with Liza Minnelli in Alvin Sargent’s quite similar, The Sterile Cuckoo). We have to empathize with this poor woman. We have to feel her fear, and marvel at her determination to live every last moment, while she selflessly shows a closed-off man how to love.

But how are we to do that when the actress comes off as less Ali McGraw and Liza Minnelli, and more Ilsa: She-Wolf of the SS. I don’t know if it’s the flat, hard eyes and those scary bald eyebrows, or that strange, blockish body (next to teeny tiny Pacino, when she gallumps up next to him and insolently rolls her shoulders, she looks like a brute ready to throttle him), or that almost impenetrable accent, or just her general off-putting attitude, but she comes off as cold, remote and thoroughly unlikeable—and that’s the death knell for this character. And indeed, the whole movie. Because if we don’t fall in love with her, like Pacino is supposed to do, we won’t buy any of this shit for one second.

And we don’t.

Read more of Paul’s movie reviews here. Read Paul’s TV reviews at our sister website, Drunk TV.