Not “horrific” by today’s standards…but acceptably frightening and strange.

By Paul Mavis

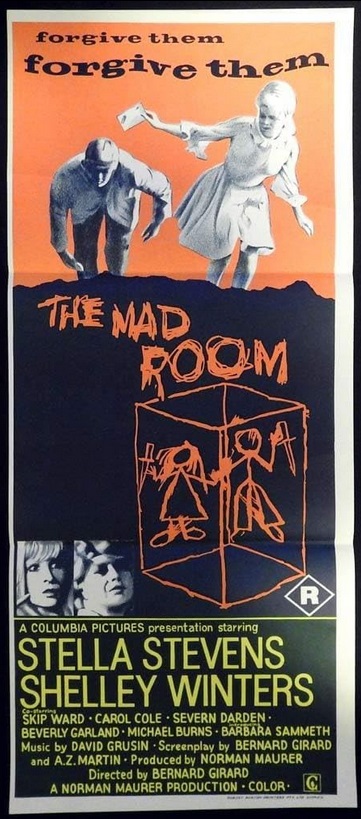

A few years back, Sony’s line of Columbia Classics M.O.D. DVDs, featuring titles from their Columbia Studios library catalogue, released The Mad Room, the 1969 remake of 1941’s Ladies in Retirement, this time starring Stella Stevens and Shelley Winters in the ghoulish tale of insane kids and murder. A staple on afternoon and late, late movie shows when I was growing up, The Mad Room may not scare me like it did when I was a kid, but it’s effective for the most part, with socko performances and a discernible, strange vibe to it that smoothes over the rough spots.

Click to order The Mad Room on DVD:

(Paid link. As an Amazon Associate, the website owner earns from qualifying purchases.)

Toronto, 1957. Two children, George (6-years-old) and Mandy Hardy (4), butcher their parents while they sleep in their beds, with 14-year-old sister Ellen the only witness to the crime. Well…the only witness to the aftermath of the crime, since the two youngest children can’t remember—or won’t tell—which one of them did it.

Jump ahead twelve years to 1969. Ellen Hardy (Stella Stevens), now 26 (come on, Stella…), works as a secretary to rich widow Mrs. Gladys Armstrong (Shelley Winters). Gladys is trying to get her pampered stepson, Sam Aller (Skip Ward), to finish an on-site museum dedicated to his Air Force general father, so the mansion and grounds of their “white elephant” home on Vancouver Island can be turned into a Air Force prep school.

Tension arises when Ellen plans to marry Sam (Gladys thinks she’s a gold-digger), so Ellen is breaking in a new maid/secretary, Chris (Carol Cole), who isn’t catching on as quickly as the demanding Mrs. Armstrong would like—something that can’t be said for Armand Racine (Lou Kane), a masseur giving “special” treatments to Gladys. Suddenly, Ellen receives a letter from Dr. Kincaid (Lloyd Haynes), of Toronto’s Hospital for Mental Ills (yep). George (Michael Burns) has turned 18, and he can no longer stay at the juvenile facility. The staff feels he’s ready to be released to society…provided he’s under the care of Ellen, with Mandy (Barbara Sammeth) along for the ride since they’ve never been separated.

Fearful that Gladys will scotch the marriage if she finds out the truth about her brother and sister, Ellen invents a story about a dying uncle entrusting the care of children to her—a lie that sickens honest Mandy. Having prevailed upon a clearly unhappy Gladys to let George and Mandy stay, events quickly spiral out of control when Gladys learns about Mandy’s and George’s imperative requirement: a “mad room” where they can “let off steam” when the “pressures” become too great (seriously…aren’t they letting today’s psychos have rooms like this now???).

It’s difficult to talk about The Mad Room beyond the simple level of “it’s good” or “it’s bad” without revealing the shocker ending (try writing about Psycho and not mention that Norman Bates is the killer, dressed as his mother…oops), so if you haven’t seen The Mad Room, and the synopsis above sounds intriguing, you should skip the rest of this review and buy or rent the movie.

It had been awhile since I last watched The Mad Room, but it was in heavy rotation on TV back when those grand guignol shockers of the 60s and early 70s starring the likes of Bette Davis, Joan Crawford, and Shelley Winters were in vogue (dipshit millennials think they discovered this trend—like they do for everything else they come across, starting with “fire” and “the wheel,” so they’ve helpfully given it a name: hagsploitation. Fuck the millennials). Utterly tame by today’s grotesque, pornographic standards, at least in terms of violence and gore, The Mad Room isn’t going to satisfy too many The Human Centipede fans, that’s for sure.

And while suitably creepy and atmospheric, The Mad Room‘s not going to fool any hardcore psychological thriller fans, either—I’ve seen William Castle chillers that were harder to figure out. But despite The Mad Room‘s obvious faults, there is this hard-to-pin-down, strange…pull that it has, a weird unreality, an artificiality (which very well may have manifested itself accidentally during the production), that somehow works. So who cares how it happened.

At least at the beginning, nothing seems to indicate that The Mad Room will be of note. From the start, the director, Bernard Girard (who prior to this outing received some note for his wonderfully oblique James Coburn-starrer, Dead Heat on a Merry Go Round), seems to betray his TV director roots. The location work in Vancouver is stunning, but the framing is all wrong, with static shots and square-headed blocking that puts everything smack dab in the middle of the image.

But very slowly, Girard starts to go in closer and closer, moving in with tighter and tighter head shots, while knocking out more and more light, until the movie feels clammily claustrophobic, with the killer finally confined to the mansion’s dark, dank basement. Although he fails to make the mansion itself a physically believable place (even though they’re obviously shooting at one), with a reality to the grounds and the interiors that would have only helped the suspense, Girard does know how to tighten the tension simply by cutting faster and faster, and letting the actors creep you out as they navigate dark hallways and stairs, and empty rooms.

As well as creating this strange physical atmosphere of a murder house by not actually referencing it specifically, Girard (who also co-wrote the screenplay with A.Z. Martin, based on the play, Ladies in Retirement) takes our basic assumptions that we bring to the story in the first 5 minutes, and plays with them endlessly until he yanks them away for the red herrings they always were. Beverly Garland has two showy, drunken scenes where she gets to play a woman scorned (her husband is Winters’ special “masseuse”), providing a tantalizing suspect for Shelley Winter’s brutal slaying (well…now we know she’s not the killer).

George and Mandy are portrayed as exceedingly polite, exceedingly controlled little killers who, just out of the nut house, act somewhat…peculiarly, with George looking up women’s mini-skirts and stalking the help, and Mandy exercising a laser-like intensity of focus that suggests she could snap at any second (it’s bad enough when Ellen asks her to lie, but when Gladys orders her out her prospective “mad room,” look out…). And both of them seem capable of violence when they physically attack each other when Gladys’ body is found, each believing that the other is capable of homicide.

Chris, the somewhat disoriented secretary, also gets in on the act, at first seeming to fear George’s stalking, but then, welcoming it, eventually inviting him into an isolated cabin to make love to him (or kill him, we may think). Indeed, even the very concept of the dreaded “mad room” itself, made to sound so ominous and necessary for the murderous brother and sister, turns out to be The Mad Room‘s biggest red herring. In a bold move, Girard never even dramatizes it; we never get to go inside the “mad room,” because it simply doesn’t exist. We never see George or Mandy use the hospital one, and they never get a new one at the mansion, because then we might truly believe they’re capable of killing…which of course they’re not, as we really knew all along (I held back as long as I could).

RELATED | More 1960s film reviews

Girard puts all of the “true” answers right up front; we just choose not to believe our own common sense because we’ve been told right from the start that either Mandy or George (or maybe even both, as the doctor suggests—another blind alley to confuse us) killed their parents. And we believe that Ellen is genuinely confused over whodunit. Yet Ellen’s little-girl curls, and her refusing to see Mandy’s logic in telling her that Ellen lives in a fantasy world of lies, are right there to see, too, along with, in retrospect, Mandy’s and George’s perfectly normal behavior (albeit as normal as it can get after spending your life in a “hospital for mental ills”).

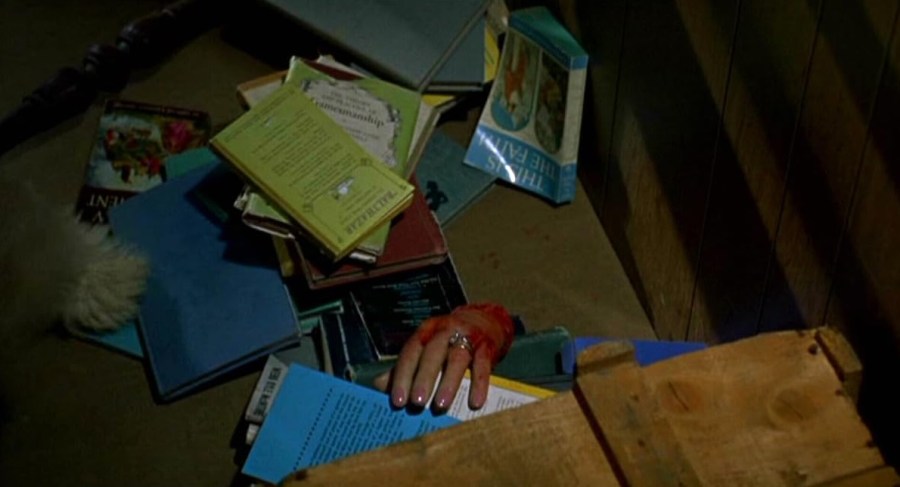

You may have guessed that Ellen was the murderer right at the start, but Girard is clever enough to make you doubt it. And then, to top everything else that came before it, Girard throws in a dog that plays “hide the bone” with Gladys’ severed hand, walking around the house and the grounds with it while we wonder where the hell he’s going to wind up putting it. It’s an utterly mad, even ridiculous little device for suspense (I haven’t seen the first movie, or read the original play, so I don’t know if this element is there), and it works, regardless of logic or taste, particularly when it leads to another killing that’s again unexpected misdirection (I won’t spoil that one…).

The cast for The Mad Room is first-rate. Unfortunately only around for the first half of the movie, Shelley Winters kills with her very first scene, where she dictates a letter while being massaged by Armand. Just watch all the little inventive, hilarious asides and double-takes she comes up with as she tries to concentrate on dictating the letter, as Armand hits her pleasure spots. It’s a remarkably funny moment from an all-time favorite of mine. Seeing Winters here, I was reminded how good, how “right” she could be, regardless of the material (god I miss actresses like her…and no, don’t try and convince me we still have them in the likes of ersatz pretenders like Kathy Bates).

The newcomers, Michael Burns (“Blue Boy”!!!) and Barbara Sammeth, have a stillness and watchfulness to their performances that are quite admirable for what could have been eyeball-rolling contest between them, while Beverly Garland is equally adept at getting across a florid character with her dignity entirely intact (another solid actress who should have had more of a career than just being best remembered for sitcom My Three Sons). And Carol Cole is just right as the slightly “off” secretary.

As for Stella Stevens, she gives a scary performance that indicates just how rarely she was used to good effect in countless anonymous TV and movie outings. Stacked and gorgeous, Stevens paid for those knee-shaking good looks by never being considered a top-flight actress (I think “sex kitten” was used more often to describe her), but as anyone who has seen The Ballad of Cable Hogue or The Poseidon Adventure knows, she had a range that was rarely tapped. Here, she comes unstuck quite nicely, pulling out one bravura scene where, very quietly, she menaces Sammeth with an exceedingly creepy speech about being able to see right through her with her all-knowing thumb. Watch her eyes; she’s believably psychotic: cold, hard and scary-unreachable. Give me a performance like this—indeed a movie like The Mad Room—over your average overhyped, relevant lecture “elevated horror” outing, any day.

Read more of Paul’s movie reviews here. Read Paul’s TV reviews at our sister website, Drunk TV.

A personal thought. I was quite friendly during th esixties with BenSchrift, at one time head of Medallion films and Shelley’s uncle. He described her as the garbage pail of the world.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have read numerous accounts that jibe with that assessment, Barry.

LikeLike