A definite change of pace for the (finally sober) staff here at Movies & Drinks…and a welcome one.

By Paul Mavis

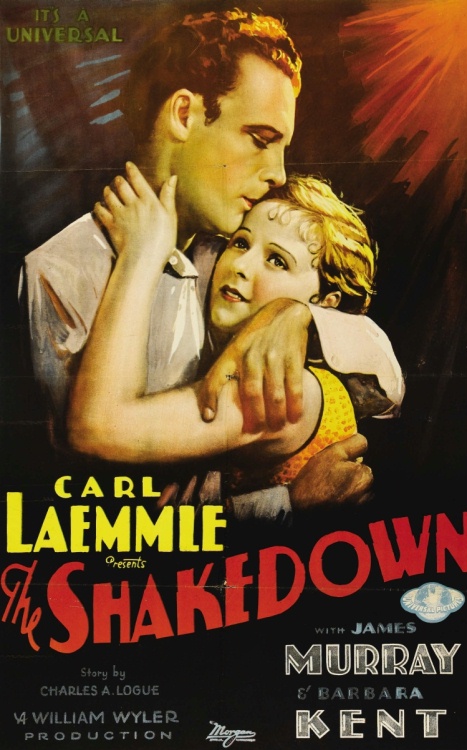

Kino Lorber (one of our favorite releasers) was kind enough to send me a brand spanking new Blu-ray edition of The Shakedown, the 1929 silent boxing/romantic dramedy from Universal Pictures.

Click to order The Shakedown on Blu-ray:

(Paid link. As an Amazon Associate, the website owner earns from qualifying purchases.)

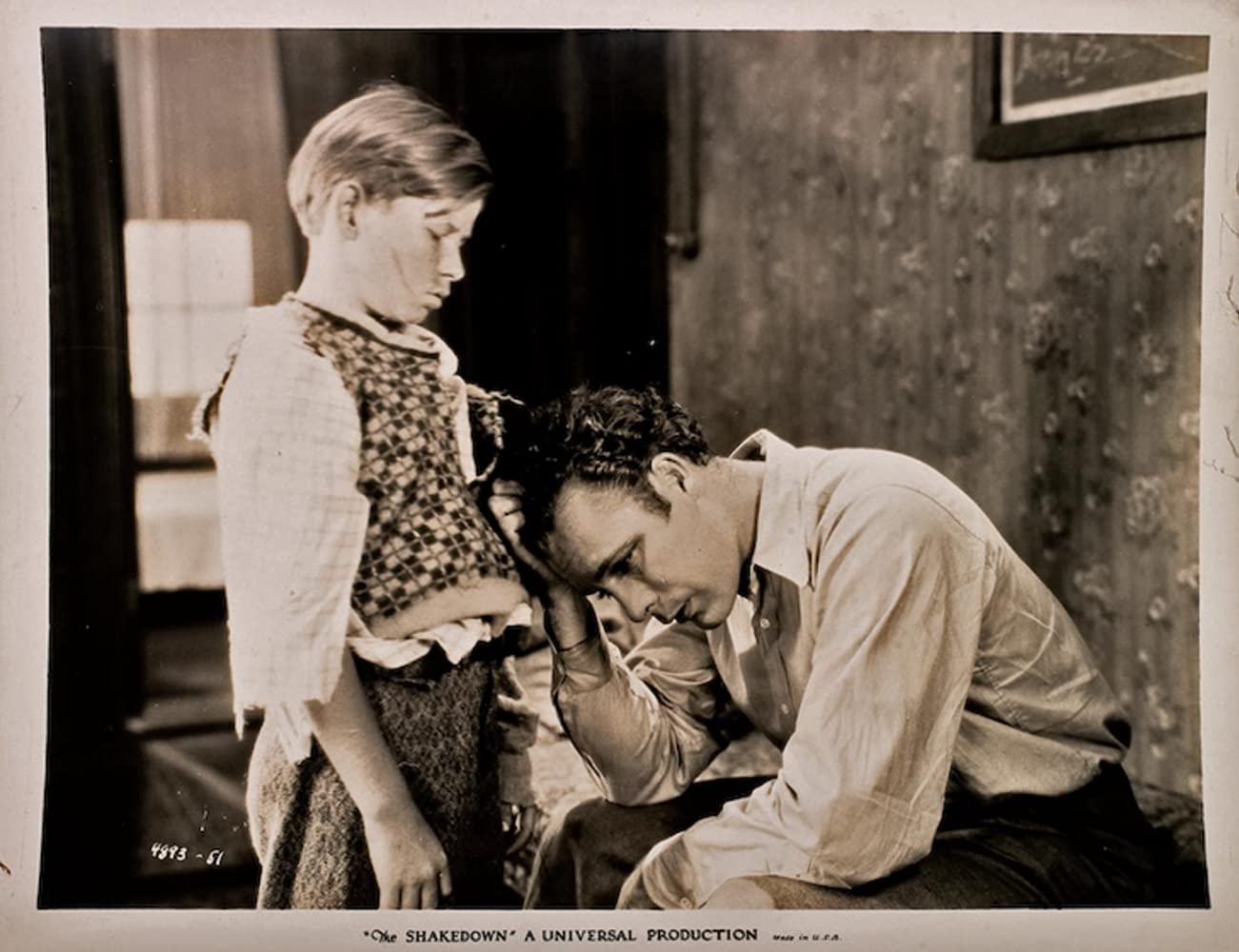

Directed by soon-to-be-heavyweight William Wyler, and starring James Murray, Barbara Kent, George Kotsonaros, Wheeler Oakman, Harry Gribbon, and young Jack Hanlon (in what should have been a star-making turn), The Shakedown is no great shakes in terms of heavy-duty “art” (whatever the hell “art” is, anyway…), but it is a cleanly-constructed, well-acted, wonderfully entertaining bit of sentimental hokum—the kind of bunk that often has more real truth in it than any self-conscious piece of “art.” Universal has done a terrific job with the new 4k restoration (there’s a very nice Michael Gatt score here), and KL has added a booklet essay and a commentary track for extras.

Drugstore cowboy Dave Roberts (James Murray) is pretty good with a pool cue…but even better with his mitts, as pug-ugly pug “Battling” Roff (George Kotsonaros) soon finds out. Nobody has laid a glove on Dave since he moved into the small town, nor can anyone beat him at a little trick he has: “knock me off my hanky.” Roff can’t, and he takes his disappointment out on a pretty little dame—something that riles Dave into socking the battler, right out on the street.

Roff’s manager (Wheeler Oakman) dares Dave to come by the “Big Athletic Tent Show” that night, where he’s offering one large to anyone who can last four rounds with Roff. Dave readily agrees, and soon the town is betting on local hero Dave…whom promptly gets knocked out in the first round. Later, the manager, Roff, Dugan the trainer (Harry Gribbon), and even the pretty little twist all split up their winnings…with Dave also getting a generous cut. You see…the whole thing was play-acting, a set-up, with everyone in on the act—all except the townspeople who believed in Dave and lost their hard-earned dollars.

Unfortunately, there weren’t enough clams for the manager’s liking; Dave spent too much time in the pool room, and not enough time with the regular sheep folks who would have readily bought into the scam. In oil-rich Boonton, the next town the grifters plan on hitting, Dave must get a job, and build up some good will with the dopes what would be giving up their pennies for good egg Dave’s uphill battle.

And that’s just what Dave does, working on an oil rig while flirting with playful beauty Marjorie (Barbara Kent), a waitress at a worksite diner. When Dave rescues (from a speeding train, no less) a little pie-thievin’ ornery named Clem (Jack Hanlon), Dave’s proto-family is all set for the big con. There’s only one problem: Clem and Marjorie really love Dave…and he loves them back. And that’s breaking grifter rule numero uno: don’t ever fall for the mark. Will their love reform and transform Dave?

Long-thought lost until a silent 16mm copy was found in 1998, The Shakedown as it miraculously appears today, is really only “half” a movie, if you will. Originally conceived and shot as a silent in 1928, Universal, liking what it saw when director Wyler delivered the picture, decided to go back and add sound effects and music throughout, as well as have Wyler reshoot several scenes with sound. That version, which ran 70 minutes according to the AFI catalog and a 1929 Variety review (which put the movie at 50% sound), and which played in the sound-equipped theaters, is now considered lost (in ’29, well less than half of the 20 thousand movie houses in the country could play talkies).

Considering the critical heft of Wyler, added with the sexy context of a disappeared silent brought back from history’s graveyard—along with the additional romantic pull of so-called “tragic” James Murray’s participation (“tragic” is a kid with cancer, not an actor given the chance of a lifetime and blowing it)—it’s too bad one can’t write that The Shakedown is a long-lost masterpiece ripe for re-discovery. That sounds a lot more exciting, right?

Well…The Shakedown is a long way from “masterpiece” status, but…who cares? Citizen Kane is unquestionably a masterpiece, but if Destroy All Monsters is on at the same time, um…I’m watching that. It’s simply a question of what’s more entertaining. Of course masterpieces can be entertaining (although that’s not a given by any stretch), but they’re always work. You have to really concentrate. You may see or hear or (gulp) think things you don’t necessarily want to at that moment. That’s fine and all, but on the whole…I’d rather have fun.

It may be a revelation to someone new to this period of moviemaking, to see an unpretentious product as technically and dramatically smooth and assured as The Shakedown, but of course to fans of the early and classical Hollywood periods, The Shakedown‘s brash, confident sure-footedness won’t come as a surprise. Even anonymous titles that were considered dreck back then can look like little narrative miracles today, compared to the often crashingly inept, intellectually masturbatory trash that has excited critics and ticket buyers for the last few decades.

The two experts that KL has employed—”film critic” Nick Pinkerton and “film historian” Nora Fiore (I want an hour-long discussion about the differences between those two job titles. Wait. No, I don’t)—seem to be at pains to find elements in The Shakedown that make it more valid, somehow, because it’s more “meaningful,” or “artistic,” or just more connected to Wyler’s later reputation (ah ha! the quicksand trap of the auteur theory!). And that’s fine. We’ve all played that parlor game. It’s fun and amusing, and sometimes it even manages to be valid. However, particularly for something like The Shakedown, I’m more inclined to enjoy it—like any good silent drama—like a poem.

Before dialogue took center stage over the (almost) “pure” cinema of the silents, at least in terms of moving along the narrative, primal, visceral, easily-grasped emotions were needed on the screen to keep the audience engaged (for convenient lopsided context, look at how much of Hitchcock’s later movies still depended on silent movie technique, while Wyler was bogged down in talky outings like The Children’s Hour, The Collector, and Funny Girl. Even his remake of Ben-Hur has an ungodly amount of yakking inbetween the spectacle). Sure, Wyler and his two editors, Richard Cahoon and particularly pro Lloyd Nosler (Ben-Hur, Flesh and the Devil), have executed a rather seamless, even at times clever, little exercise in continuity here, but what is it in service of? Those broad, elemental emotions the characters wordlessly express.

The Shakedown‘s opening act sets the stage for a hard-scrabble Depression-era meller of smirking grifters who travel from town to town, fleecing the suckers by playing off their emotions (rooting for the underdog hometown hero…while trying to make an extra buck, too). That depressing, downbeat undercurrent runs throughout the movie, from plucky Marjorie having to sling hash for long hours in the middle of an ugly oil field (and certainly having to fend off at least one or two roughnecks who aren’t as polite as Dave), and homeless, parentless (why does the disc commentator call him a “latchkey kid”?), starving Clem, stealing a pie to survive (and finally eating one off a plate like a ravenous dog—no hands), to Dave again, who goes from lying fall-down artist to real-life boxer, who must endure a brutal beating—and then give one—to save his very soul. There’s nothing sentimental about the world in which these characters exists.

That underlying grit only makes the laughs, and the romance, and the sweetness of The Shakedown that much more pronounced. Neither Fiore nor Pinkerton mention enough how consistently amusing The Shakedown is; it’s as much a comedy as it is a drama or romance or sports picture. Wyler and writers Charles Logue and Albert DeMond never let up on the funny throwaways, such as the Deacon chalking Dave’s chin before he tries to belt it (and nicely, Dave laughs along with everyone else), or Marjorie’s quick-thinking “No Sale” cash register answer to Dave’s persistent wooing, or Clem and Dugan’s hilarious face-pulling (unlike Pinkerton, I enjoy slapstick), or my favorite: Dave physically shutting Clem’s mouth when the little terror is cussing out Dugan.

The humor isn’t just bald, though; Wyler’s touches of ironic, even cynical humor come at unsuspecting moments, such as Clem’s reaction when Dave asks if anyone else saw him rescue Clem from the speeding trains (Clem takes a minute and realizes Dave’s question isn’t entirely innocent, and the boy grins the grin of one schemer recognizing another). That realization is doubled back when Dave, watching Clem shoot dice (they’re loaded, which he doesn’t realize at first), smiles behind the boy’s back when Clem says Dave needs someone to look out for him. Dave the grifter knows exactly what Clem the survivor is…but Clem has no idea Dave’s more dishonest than Clem.

Equally affecting are the lovely scenes of genuine tenderness and sweetness—found in so many movies from that earlier era—that would never show up in today’s mainstream movies, largely because younger audiences have been trained to sneer at such emotions, to distrust their sincerity and genuineness (to be supremely, even cosmically ironic, to be deadpan and uninvolved except when a mob gang-up on a “cancel-it-all” social media flavor of the month is called for, seems to be a genuine career goal for many millennials). The heartbreaking shot of Clem, looking through Dave’s window, dying for some affection from a father figure who just saved his life, is elevated to a fleetingly transcendental experience as Wyler has the lace curtains blow back and forth against the open window—a gossamer barrier to Clem’s happiness which may as well be iron bars…if Dave rejects him. For just a moment, at the amusement park, as Dave and Marjorie spin away from us on the Ferris wheel, we’re given too-brief glimpses of other couples on the ride, in various states of delight, as they flicker like a film strip (it’s a pity this whole date scene wasn’t longer).

It’s verboten today to have women “merely” be supportive and redemptive figures (that’s working out well…), so luckily, we have those achingly beautiful shots of Marjorie, loving femininity personified by Barbara Kent, as she pleads for Clem’s future with the truant officer (she’s no pushover, getting right in there to protect Clem during his fistfight…as if he needed that), and when she tries to fathom the hurt caused by Dave when he confesses his sins, and rejects her (a powerful scene for an agitated Murray, nicely contrasted by quiet Kent). Later, when she cuts right to Dave’s problem—”Dave…did you ever really try?”—her forgiving kiss is both restorative and erotic. Saying that Kent has little to do here, an observation seen through our current aesthetic context, is wide of the mark, and sadly, to be expected.

Those scenes with Murray and Kent are palpably emotional precisely because there’s no dialogue to clutter it up; we’re concentrating on their faces, their eyes, their expressions—the great gift of silent movies (silents of course were never meant to be entirely silent, so a musical score—abstract compared to dialogue—only enhances, not intrudes). Wyler’s camera (with the aid of cinematographers Jerome Ash and Charles J. Stumar) is frequently kinetic (sometimes too much, like that erratic, almost hand-held shot of the billiard break), particularly during the wild boxing matches. They have a primitive power that looks like a direct antecedent to Scorcese. Many writers comment on the famous oil rig scene, where Murray rides to the top of the derrick on a cable. It’s dynamic, no question, but I find the scene that follows far more powerful. Through a series of crosscuts, Dave at the top of the derrick and Marjorie down below at the diner, wave to each other, before Marjorie laughingly pantomimes putting her arms out…to catch a falling Dave. What better foreshadowing could there be of the humor and loving redemption that will play out in The Shakedown?

Just a quick note about the Kino Lorber disc and extras. Even though The Shakedown survives from only 16mm source material, Universal has done a remarkable job with their 4k restoration, which is nicely showcased in KL’s Blu transfer. Grain is smooth and filmic, and the gray scale is subtle. Fine detail is discernible (within the limitations of the cameras then used). As for the extras…”The Nitrate Diva” (oy vey these verkakte marketing monikers) at least writes like she enjoyed the movie, even if she’s prone to flowery phrasing and inexact adulation. She gets credit for enthusiasm. Pinkerton, on the other hand, in a droning, pedantic snoozefest, makes the 65-minute The Shakedown seem like it’s three hours long. Why do these commentary tracks always feature people who sound alternately bored or sneering? Do any of them actually, truly love movies? Would it kill you to sound at least mildly happy to be doing what you’re doing?

Most of the commentary track is made up of Facts on File lists of credits and names one could easily get online, with few observations about the movie itself. And excuse me but what the hell is “meta” about Wyler casting actors who look like con men? He should cast actors that didn’t? Can we please digitally erase the word “meta” from all future movie reviews? When I was in school it was called “self-reflexive” and we thought we invented some new way of looking at things (we didn’t). If Pinkerton’s sign-off is for real—”I leave you to go on my merry way…undefeated champ of the commentary track,”—we are doomed as a society.

Read more of Paul’s movie reviews here. Read Paul’s TV reviews at our sister website, Drunk TV.

The film and your assessment make me rush to order, but the commentary tracks and not just in this instance, have, for the most part, left me cold; never put on a commentary track unless it’s David Kalat, who not only does his homework, but has a good voice to match his insightful material.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Agreed.

LikeLike