Considering it’s now official that we live in a Third World banana republic (when the illegitimate ruling junta doesn’t even bother to cover its tracks when trying to zap its chief political opponent, the “golden days” of the American republic are well and truly over), can you blame anyone who’s looking for a little escapism? A little lightness, some fun, to forget how close we truly are, to the jungle?

By Paul Mavis

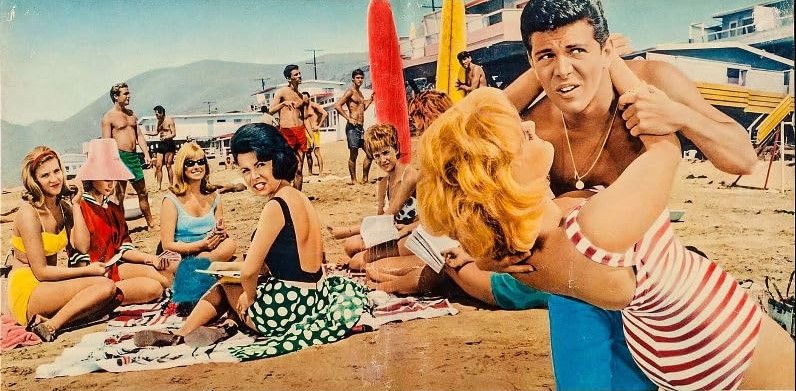

Thank god for Frankie and Annette. A few years back, M-G-M and 20th Century-Fox re-released four of the celebrated Midnite Movies flipper disc double-features, and packaged them in a boxed set titled, Frankie & Annette: M-G-M Movie Legends Collection. Heading up the collection, which includes 1964’s Bikini Beach; 1964’s Muscle Beach Party and 1965’s Ski Party; 1965’s Beach Blanket Bingo and 1965’s How to Stuff a Wild Bikini; and 1966’s Fireball 500 and 1967’s Thunder Alley, is Beach Party, from 1963. A cartoonish teen musical, brought in on the super-cheap with zero expectations, and which went on to become a huge hit, Beach Party is a time capsule from a more innocent—though no less knowing—time, which still delivers a good number of laughs. The songs are fun, the cast spirited, and the atmosphere light and fluffy.

Click to order Frankie & Annette: M-G-M Movie Legends Collection on DVD:

(Paid link. As an Amazon Associate, the website owner earns from qualifying purchases.)

During the early 1960s, in that sweet screen time spot between the existential angst of Brando and Dean, and the coming counterculture revolution starring the likes of Hoffman and Fonda, Walt Disney and Doris Day ruled the suburban movie screens and drive-ins of America, along with American International Pictures, home to Vincent Price and rubber monsters and tame teenage punks like John Ashley. Although they became the signature studio for the “beach movie” subgenre, AIP didn’t invent it, as is often incorrectly cited (Gidget had been a big, big hit for Columbia and Sandra Dee back in 1959, and you could even make a case for the Hope/Crosby Road pictures being a related antecedent).

Had AIP founders Samuel Arkoff and James Nicholson had their way with Beach Party, as originally written by Lou Rusoff, it would have stayed comfortably within the traditional AIP exploitation guidelines of troubled kids and plenty of sex, not at all unlike Rusoff’s numerous other AIP efforts, including Girls in Prison, Runaway Daughters, Dragstrip Girl, Motorcycle Gang, and Hot Rod Gang. However, when William Asher (producer and director of TV’s Bewitched) was approached to direct, he wanted Beach Party to represent all the kids out there who weren’t having a particularly hard time adjusting to adolescence.

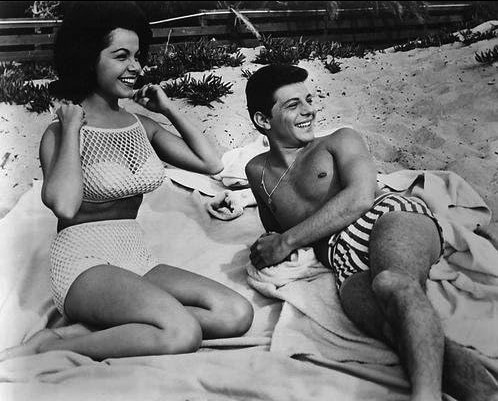

He wanted to market a romantic musical comedy to the majority of kids out there who—despite what Hollywood thought—played by the rules, who enjoyed their carefree summer vacations away from school, and who engaged in the same kinds of age-old, yet essentially innocent, sexual give-and-take games that “teenagers” Frankie Avalon (23-years-old at the time of shooting) and Annette Funicello (21-years-old) acted out on the screens. With their teasing suggestions of having sex (but never actually going through with the act), and their farcical attempts to make each other jealous with other temporary partners, Frankie and Annette were the teenaged equivalent of cinema superstars Rock Hudson and Doris Day, providing ever-so-slightly naughty thrills in a decidedly innocent package, aimed directly at the teen fans who may have thought older Doris and Rock fun…but definitely “squares” like their parents.

I suspect that most critics today would describe these movies as out-and-out fantasies, and they’d be right, up to a point (oh, and don’t forget today’s jejune stand-bys: “racist” and “misogynist,” too…). Of course, some kids back then had premarital sex; they got pregnant by accident; most kids had to work during their summers (something the stealth-wealthy “beach party” kids never do); and their relationships were fraught with real emotional crises, as opposed to the “wink wink” goofiness of these comedies. But most movies idealize or at least romanticize their subjects (in just a few years, Warren Beatty and Arthur Penn would hoodwink critics who should have known better with the engagingly romanticized Bonnie and Clyde).

As well, it’s important to remember that back in 1963, teenagers were, believe it or not, expected to act differently (i.e.: “civilized”) than they do now…at least on the surface. So it’s not surprising that kids back in the early and mid-60s went for these “beach party” movies in a big way. They recognized up on the screen kids not too much different from themselves. Girls nodded in agreement as they watched Annette fend off the always amorous but commitment-shy Frankie, while guys suffered along with Frankie, wondering why their girlfriends weren’t more “accommodating” before that ring went on their fingers. These movies have been completely written off as camp nonsense, but like anything that’s good that lasts, there are real truths at their cores.

Viewed today, the “beach party” movies offer a hermetically sealed cinematic world of bikini-clad babes, dancing in the sand, singing along with Frankie and Annette in between their eternal battle of sex before commitment, while fending off the distinctly non-threatening threats of oldster cycle punks the Rats and Mice, led by Eric Von Zipper (Harvey Lembeck). Proof positive that the “beach party” movies—and the teenagers of the early sixties—had moved beyond the original teen rebels Brando and Dean, Von Zipper and his henchmen are viewed as ridiculous throwbacks to an era that no longer fits in with the California sun, music and surf of these healthy, relatively well-adjusted kids (at least in terms of propaganda, one should also include in that formula the whole Kennedy/Camelot zeitgeist that was being so effectively promoted the media).

RELATED | More 1960s film reviews

Von Zipper, overweight and relatively “ancient” (Lembeck was 40 when Beach Party was shot)—two huge no-no’s in the teen world—represented the leather-clad punks from the early 1950s who never outgrew their “rebellions without a cause,” an existential state of uncertainty which seemed all the more ridiculous to audiences when set against the tanned, scantily-clad, happy teenagers they tried to menace. Hot dogs and soda pop (never beer), dancing in the sand, singing duets on the beach, while having cool adventures drag racing, skydiving and downhill skiing, were the fantasy movie expressions for suburban teens in the early sixties (fueled also by the explosion of California surf music by groups like The Beach Boys and Jan & Dean), before the cinematic world changed again with the counterculture chic of the late 1960s.

Now…on to Beach Party. On the spectacular beaches of Malibu, California (specifically Paradise Cove), teenagers Frankie (Frankie Avalon) and Delores (Annette Funicello) arrive at a secluded beach house for a fun summer vacation. Horny Frankie secretly intends for it to be a “private” vacation, but Delores tricks him and invites the whole surfer gang to stay there, as well. Frankie, upset with Delores’ stalling tactics, gets advice from the other guys, who tell Frankie to “put her down” by going out with another girl; in this case, the Marilyn Monroe look-alike, waitress Ava (Eva Six).

What the kids don’t know is that their frolics on the beach are being filmed and audio recorded by Professor Robert Orwell Sutwell (Bob Cummings), an anthropologist/sociologist studying the American teenager for similarities with more “primitive” native tribes. Aided by Marianne (Dorothy Malone), his attractive assistant (who has feelings for the dense professor), Sutwell feels he needs to get closer to the group to truly understand their lingo and “mating habits.”

Going to the popular hang-out Big Daddy’s, run by beatnik poet Morey Amsterdam’s Cappy Caplan (“I will walk among you”), Sutwell rescues Delores from aging “Wild One” motorcycle gang leader Eric Von Zipper (Harvey Lembeck), by utilizing a potent “Oriental Physio-Psycho Philosophy” maneuver called the “Himalayan Time-Suspension Technique,” rendering Von Zipper paralyzed. Delores, seeing an opportunity to make Frankie jealous, is taken with Sutwell’s gallantry, and falls for him.

Meanwhile, Marianne, jealous of Sutwell’s increasing attention to Delores, decides to leave his employ, while Sutwell fends off the misguided attention of Delores, who essentially agrees to be “his first.” When Von Zipper returns at night to kidnap Delores, he fails, but Delores and Sutwell are caught in an innocent, yet compromising position. Frankie confronts the Professor at his beach house, and discovers the gang is being used as case studies by Sutwell. But Sutwell sets the record straight about Delores, just in time for the gang to protect him when Zipper’s “army” comes to pound the Professor and the surfers.

All of the ingredients for later “beach party” movies are found here in Beach Party, a formula that AIP would mine until the series burned out four short years later. The opening sequence, with Frankie and Annette singing the catchy theme song, immediately sets the circumstances and tone of this piece, as well as for subsequent sequels. School is over (at least temporarily); money or a job is not a concern (Frankie has his car and neither one ever mentions money needed for food or entertainment); parents are nowhere in sight (one assumes they’re either high school seniors or college freshman); the beach is free of people (they shot these movies during the freezing winter, when the beaches were empty); and we’re alone…so let’s let nature take its course. As the song says, “Vacation is here! Beach party tonight!”

And while Annette and Frankie try to force each other over to their own way of thinking (Marriage=happiness; sex before marriage=necessity), the songs keep coming. Legend Dick Dale and the Del-Tones show up, playing some wicked guitar riffs, while Frankie and Annette get their own numbers, as well. The title tune is the best, but Frankie’s Don’t Stop Now, with some eye-catching female dancers, is a highlight, too. However, I would imagine quite a few women viewers today will look askance at Annette’s pre-feminist Treat Him Nicely (they can always bitch about it to the cats). Even Malone gets in on the act, singing (rather badly) along to a recording of Annette doing Promise Me Anything.

It’s easy to see why Beach Party was such a success with kids back in 1963 (grossing in the neighborhood of $4 million on a budget of less than $400k). Funicello and Avalon, both highly personable performers (and big stars already with the teen crowd), have a natural chemistry together. They’re such a cute couple, smiling a mile wide across the Panavision screen while singing the title song, that their appeal is infectious. What parent wouldn’t lend their kid a couple of bucks to see those nice kids have a good time at the beach?

Headliner Bob Cummings brings quite a bit of improvisational finesse (according to Asher) to his funny, stuffy character; lines like, “It’s the Samoan Puberty Dance all over again,” and “Aggression…definite aggression” as he watches Von Zipper wind up, are consistent laugh-getters. It’s a shame he wasn’t recycled like the rest of the cast in the following sequels. However, the talented, gorgeous Malone is utterly wasted as Marianne; her part is so small and insignificant, it’s a wonder the Academy Award-winning actress took it in the first place. And Lembeck, as expected, is quite funny as the retro-Brando wannabe, Eric Von Zipper, who refers to anyone in earshot as “You stupid,” and who gets the best line of the movie when, while watching his Rats and Mice get creamed by the surfers, he says in wondrous Brooklynese, “I got an army of stupids!”

William Asher, shooting and editing for maximum incoherency, keeps everything light and breezy, maintaining an admirable cartoon anarchy to many of the scenes. Lembeck is the most obvious choice for such visual exaggerations (later on, in Beach Blanket Bingo, he’s cut in two by a buzzsaw), with his “sickle” having a mind of its own, and of course, Zipper “giving himself ‘the finger'” learned from the Professor’s Himalayan Time-Suspension Technique (did kids back then laugh at that silly, tame joke?).

The deliberate aping of silent movie gags and pacing (silent comedies were once again popular on product-hungry early sixties television, as well as being repackaged with sound effects and music by movie producers like Robert Youngson), a technique repeated and expanded throughout the series, no doubt tickled the young audiences as both corny and funny. After all, as anyone who has seen a Three Stooges short recently can tell you, a pie fight (the finale of Beach Party) is always going to get laughs. No doubt good-natured guffaws were elicited from the ridiculously fake rear-projection scenes of the principles surfing, as well (movie audiences weren’t any more technically naïve back then, as they are now).

Innocence, high spirits, a sense of freshness and youth, and cinematic ineptitude of the highest (and most delightful) order, mark Beach Party as a goofy drive-in classic, and a legitimate icon in the exploitation ranks of American movies.

Read more of Paul’s movie reviews here. Read Paul’s TV reviews at our sister website, Drunk TV.

Well observed regarding the film and the world.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Barry

LikeLike