Next Tuesday is the 70th anniversary of the death of actor James Dean (Google him)…which is probably going to elicit hardly a peep on social media, where such trivia are now noted by posters desperately looking for hits, facilitating amateur “comedian commentators” to make insufferably lame jokes, and where certifiably insane advocates—for every cause and outlook and malady imagined—can take a historical event and “make it personal” via an unhinged rant. We live in nauseating times, to be sure.

By Paul Mavis

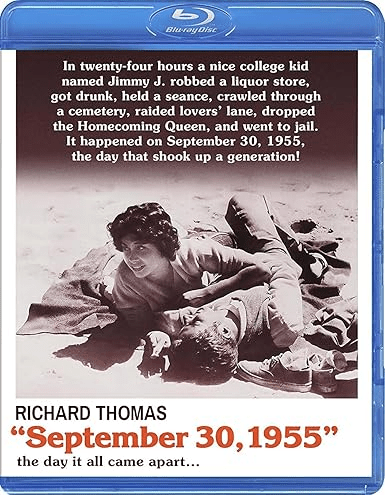

While not a particular fan of Dean’s acting (more on that below), his upcoming death anniversary did make me think of a movie tied in directly with that event: Universal Pictures’ 1977 drama, September 30th, 1955 (originally titled 9/30/1955), written and directed by James Bridges, and starring The Waltons‘ Richard Thomas, Susan Tyrrell, Deborah Benson, Lisa Blount, Thomas Hulce, Dennis Quaid, Mary Kai Clark, Dennis Christopher, and Collin Wilcox. A coming-of-age drama with some potentially interesting ideas about celebrity and how (some) teen fans react to it, September 30th, 1955 came and went with little fanfare from ticket buyers, but it’s worth a look in contrast to today’s performative culture, where actors have been replaced by their clinically narcissistic fans as the “stars” of their very own online movie-lives.

Click to order September 30th, 1955 on Blu-ray:

(Paid link. As an Amazon Associate, the website owner earns from qualifying purchases.)

It’s the night of September 30th, 1955. Arkansas State Teachers College (The University of Central Arkansas) college student Jimmy (Richard Thomas) sits in the Conway Theater and cries over East of Eden, starring James Dean, for the fourth time. The next morning, on the football field, “Jimmy J” hears on a nearby radio what he thinks is an announcement that his hero, his idol, James Dean, has been killed in a car crash the night before.

Distraught, he leaves the practice field, running to his girlfriend Charlotte Smith (Deborah Benson) to (unsuccessfully) get a dime to make a phone call. Bumming a coin off hero-worshipping wimp, Eugene (Dennis Christopher), Jimmy calls Billie Jean Turner (Lisa Blount), a dramatic, unconventional girl from the “wrong side of town” who he’s friends with, and who shares his obsession with James Dean. The line’s busy.

Once he confirms Dean’s death at the radio station, and tries Billie Jean’s line again, he gets her mother, fun-lovin’ Melba Lou (Susan Tyrrell), who primes him that movie-crazy Billie Jean is beside herself with grief. Billie Jean says she’s been staring at pictures of Dean all night, and crying, and trying to contact his spirit, and she begs Jimmy to come and get her—she needs him.

Jimmy, along with Charlotte, friends Frank and Pat (Dennis Quaid, Mary Kai Clark), and Jimmy’s roommate, car-owning Hanley (Thomas Hulce), drive out to get some food before picking up Billie Jean (whom the others aren’t too thrilled about picking up, particularly a wary Charlotte). When Charlotte can’t understand why Jimmy is so upset over “just” a movie star, Jimmy flips out and almost leaves, before rejoining the group.

Swinging by Billie Jean’s run-down house, it’s a real scene, with Melba screaming at Billie Jean that she’s locked up inside until she does her chores, and Billie Jean screaming out her bedroom window at her mother, repeating over and over again that she’s a pissant. The nice, polite, rich college kids—including Jimmy—aren’t impressed, and decide to leave, with a disgusted Jimmy suggesting they get some alcohol and go have a party.

When underaged Jimmy is denied some Old Crow, he ups and steals it, with the state police giving chase to the screaming teens. Ditching it to the Arkansas River, the kids start a fire and get to drinking, with Frank and Pat sensibly making out, while Jimmy “acts out” his grief, stripping down to his BVDs, and covering himself in mud. Hanley says he’s grieving like the “mud people” in a National Geographic, but sensible, cynical (and sexy) Pat calls it correctly: he’s just doing it to be “different.”

Before they can have Jimmy’s “ceremony” involving a mud Oscar statuette, the cops come and the kids lam it out of there. Back on campus, Frank and Pat break off with Jimmy, calling him on his phony shit, but Charlotte agrees to continue the séance at her house…even though Jimmy intends on inviting the unstable Billie Jean.

Before that can happen, a nearly-naked Jimmy is humiliated in front of his mother (Collin Wilcox), who stopped by his dorm to pick him up for a visit. Shocked at his drunken appearance, she fears he’s going to turn out just like his missing father: a loser. And worse (from Jimmy’s viewpoint): she can’t understand his grief over an actor he’s never met. She just doesn’t understand him (sigh).

That night, Jimmy, Charlotte, Hanley, and tag-along Eugene pick up an over-the-top Billie Jean (she’s dressed like Dean favorite, Vampira), and decide they need to do more than just conduct a séance to honor Dean’s rebellious spirit…which results in a tragedy that changes all their lives.

September 30th, 1955 was one of those Showtime movies I’ve written about before: never-heard-of titles that I watched over and over again when we first got the premium cable service, when the proposition of watching any movie, no matter which one, uncut and free of commercials, was a singularly unique experience. If September 30th, 1955 ever opened in theaters in my area, I missed it (I couldn’t find it in my local paper archives), but it wasn’t some no-name indie that escaped out into theaters through some small distributor, either.

September 30th, 1955 was, after all, the follow-up to writer/director James Bridges’ 1973 critical hit, The Paper Chase, for which Bridges’ script was nominated for an Academy Award, and for which John Houseman won the Best Supporting Actor Oscar. Producer Jerry Weintraub had just helped guide Robert Altman’s Nashville to multiple awards nods and a big, healthy b.o. gross. Cinematographer Gordon Willis took time out to lens this in between working with directors like Francis Ford Coppola, Woody Allen, and Alan J. Pakula. And it starred Richard Thomas, the star of Top Ten television hit, The Waltons, in his first movie foray after the success of his series. Universal had every right to think they may have had a potential winner in September 30th, 1955.

While it received some respectful notices (The New York Times‘ Vincent Canby was guardedly generous), September 30th, 1955 came and went without the slightest trace at the box office. Why? It’s always hard to say. The six-month production delay (Thomas broke his ankle riding the motorcycle) didn’t help, moving back a more appropriate summer/fall release to the wintery January graveyard.

Not putting either Dean’s image or Thomas’ on the poster and promotional materials was a stupid move, too. They could afford a clip of East of Eden in the movie itself, but they couldn’t put Thomas staring at Dean on the poster? And why isn’t your biggest draw, Thomas, even on the poster? Everyone knew his face back then, from The Waltons. Strange move by Universal promotions, surely.

Then again…maybe September 30th, 1955 was just too much of an anti-American Graffiti / Happy Days period downer to generate much interest from the studio post-production…or word-of-mouth at the box office. Fraudulently promoted like some kind of drive-in actioner (check out the ad copy on the poster…and the trailer is designed to make the movie look like Jimmy J and friends are returning to Macon County), what September 30th, 1955 is instead, is a morbid, relatively interesting coming-of-age movie that tantalizingly suggests a connection between kids’ behavior and their idolization of movie stars…but then cuts out before exploring that.

It also, surprisingly, has very little to do with James Dean (maybe that was a factor, too). If you’re tuning into September 30th, 1955 because you’re into Dean, you won’t find anything but the slimmest references to those accepted, common clichés about his appeal to disaffected teens or the “death cult” he inspired that supposedly “transformed” so many young lives. Which was fine with me, since I never thought Dean was much of anything in comparison to his contemporaries like Brando and Clift (all the mugging and the face-pulling, and the phony “Method” theatrics masquerading as “truths”…and jesus, the crying). Death, as the old showbiz saying goes, was Dean’s greatest career move.

Bridges’ screenplay keeps obsessed Jimmy J relatively incoherent about what, exactly, is Dean’s impact on him and the world, outside of the clichés about similarities in their personal backgrounds. When cynical voice-of-reason Pat (sexy local actress Mary Kai Clark makes quite an impression here—too bad she didn’t go on to other roles) says many people think Dean’s just an imitation of Brando, Jimmy rears up and retorts, “A lot of people are jealous and full of shit!” Not exactly elucidating on Dean’s import. Quaid, equally unimpressed with Jimmy’s grief, sneers, “You sure are making a big fuss about a neu-rotic movie star.” Bingo.

Bridges seems to want to get at how someone like Dean can affect kids in an increasingly media-dominated age, with “regular” kids like Pat and Frank not affected at all, Charlotte and Hanley liking Dean but certainly not in grief over his death, and “unstable” kids like Jimmy and Billie Jean susceptible to outsized behavior because of Dean’s influence used as an excuse for their acting out.

Even an embarrassed Jimmy admits it’s “crazy and dumb” to feel this way about someone he’s never met. When he’s met with sympathy by kind Charlotte, though, he reverses tack and angrily states he feels “cheated out of all the great things [Dean] would have done, and I’m never going to see it.” Jimmy doesn’t really want true understanding from Charlotte; he wants to be the image he has of cinematic Dean, gleaned from movie magazines and articles: tortured, sensitive (in a world of people who aren’t) and most assuredly not understood by the likes of nice-but-square Charlotte. He doesn’t want reality. He wants teen-aged angst, amplified by glamorous, phony Hollywood p.r.

September 30th, 1955 is quite good at showing the escalating unstableness of Jimmy, particularly when he finally and fully aligns with genuine kook, Billie Jean. Bridges is careful to draw firm social distinctions between the two groups, to show Jimmy’s “improper” (according to his group) attraction to Billie Jean. If you were in college in 1955, you had to have had some money (Hanley has a sweet Chevy courtesy of his parents, while Charlotte is loaded, her father being a State Senator).

Jimmy’s father may be absent, but his mother’s family must have dough, since she’s springing for college. So her gentile, Southern sensibilities are shocked when she sees him drunk and almost naked out of the dorm lawn, behavior that wouldn’t surprise any of his friends if attributed to “low class” Billie Jean.

Charlotte may feel threatened by Billie Jean’s influence on Jimmy, but she’s clear she doesn’t see Billie Jean as competition—she states she feels sorry for Billie Jean, considering her reputation and the “kind of mama” she has, the implication being that Billie Jean may be as “loose and fun-lovin'” as her mother (Hanley tells everyone he heard Melba Lou had Billie Jean when she was 13-years-old).

Susan Tyrell’s Melba Lou is a delight, a real burst of energy in a relatively quiet movie (that breathy voice when she answers the phone, hoping for a gentleman caller, only to have her later exclaim in mock terror, “My…my god my beans are boiling over!” is irresistible). But regardless of how sharp Melba Lou is in seeing through Billie Jean’s antics, she’s more preoccupied in reliving her past romantic successes, and not focusing on what Billie Jean needs in a mother (when Billie Jean, dressed outrageously as Vampira, descends her stairs, she tells a nervous Jimmy not to worry: her mother won’t notice. And Melba Lou doesn’t; she’s too busy getting a neck message from a date).

Bridges makes it clear that Jimmy enjoys breaking the established rules of his class status by hanging out with Billie Jean (Charlotte calls it correctly: Jimmy’s behavior becomes more unacceptable—by hers and Jimmy’s group’s standards—because Billie Jean “eggs him on,”). Watch the excitement that Richard Thomas conveys whenever he speaks with Billie Jean about whatever crazy shit she’s laying on him at the moment (Thomas, an excellent, evocative actor, unfortunately never crossed over into big screen stardom, as he should have).

She’s exciting to him, not conventional Charlotte, who worries about things like her mom’s carpet (during the séance they spilled candle wax on it). Billie Jean wants to act out her deliberately pumped-up feelings, no matter what (she has no trouble groping Jimmy’s erection when they embrace). Charlotte, on the other hand, angrily stops Jimmy from touching her breasts, even after he reaches her emotionally at the séance.

RELATED | More 1970s film reviews

Rebellious Jimmy’s growing attraction to the unconventional, and to acting out, just needed a person like Billie Jean to bring it forward, with the Dean obsession a convenient hook for both of them to use as an excuse for their behavior. To his credit, Bridges makes it clear that Jimmy’s and Billie Jean’s contrived actions are obvious and spotted by not only the adults, but their teen contemporaries, too.

When Jimmy doesn’t get the reaction he wants from his friends, when he speaks reverently about Dean at the river, he ups his game, stripping down and covering himself in mud, and making a mud totem, intoning—with a completely straight face—that Dean “will never die. He is immortal. Give us a sign, Jimmy!” His friends, however, aren’t buying it at all. Leave it to wise, disgusted Pat to lay it out straight to a sheepish Jimmy, when they return to campus: “I think you’re sick. And I think you’re affected and I think you’re weird. And I think Charlotte oughta have her head examined for going with you.” Frank offers an equally assured, “Ditto.”

Even sympathetic roomie Hanley agrees with them, allowing that everyone is affected in some way. He, however, is balanced enough to laugh that truism off, inviting Jimmy to do so, too. Jimmy does…but he can’t stop at this point.

You can’t blame Jimmy, though, for wanting to act out, considering his mother’s continued disappointment in him (wishing he were more “good”) and his staid life at college, where his coach lectures him on suppressing individualism in favor of some bullshit “team effort” philosophy that “won the war and keeps the peace.” What bored, growing-pains teen wouldn’t at least turn his or her nose up at that?

Melba Lou is just as aware as Pat when it comes to teens acting dramatic. Constantly referencing Billie Jean’s obsession with movies (versus reality), she states it simply: when she details Billie Jean’s extravagant expressions of grief over Dean, she offers, amused, “She sure gave one of her better performances.” In other words, Billie Jean has done this many times before. Could that be because Melba Lou doesn’t give Billie Jean the stability she needs, so she acts out?

Sure, why not…or maybe Billie Jean is just dramatic and unstable. When she discusses the séance with Jimmy on the phone, she’s not sad at all; rather, she’s delighting in her own anticipated actions: “This has to be a very special night. I have to think, and give myself up to my own imagination,” she enthuses. Either way, the Dean obsession, Bridges seems to suggest, is just a convenient vehicle for Billie Jean’s increasing need to act out.

Indeed, once the séance starts, Billie Jean’s grief for Dean is clearly no longer the point—ordering around “social better” Charlotte while acting weird and strange on the “darkest night of her life,” is. And that need to act strange and “perverse” (in relation to the sedate, respectable 1950s culture) is attractive to repressed Jimmy, who follows her lead.

How repressed Jimmy is—or perhaps, in what way he’s repressed—is unfortunately one of the more interesting tangents of September 30th, 1955 that doesn’t get more thoroughly explored. There are clues throughout the movie that suggest Jimmy may be inching towards acknowledging there is a closer connection to his bisexual (or just gay, depending on what sources you choose) hero, James Dean, than Jimmy may realize.

The first shot of Jimmy is him looking lovingly, even adoringly, at James Dean’s image up on the movie screen, crying along with the movie…and being embarrassed when he realizes others may see (that image alone may have instantly turned off Thomas’ large contingent of female teen fans). When he tells Charlotte how affected he was by Dean’s influence, he states he even thought of trying out for a school play, the line delivered in such a way as to suggest how outrageous and out-of-character such a thing would be for a wealthy, football-playing straight like Jimmy J. to do.

In Billie Jean’s bedroom, the obviously turned-on Jimmy can’t act on his groped erection, pulling away from a teasing, aggressive, frankly sexy Billie Jean, who chastises him in the worst way possible: “You’re scared. I don’t think Jimmy Dean would have pulled away.” Indeed, the only girl he pushes the limit with, sexually, is straight-laced Charlotte. He knows she’s going to say, “No!” when he tries to hold her breasts.

At the séance, when horny-yet-kidding (maybe?) Hanley goes after a terrified Eugene, suggesting oral sex, Jimmy is disgusted and pissed off—but not because of the act itself. He only objects to screwing around like that during the séance (later in the movie, he’ll flat-out state he loves Dean). That suggestion was disrespectful to Jimmy J…not objectionable (indeed—he’s more pissed off at the “regular” boy-and-girl couples making out near the cemetery, which he somehow conflates into disrespecting him and Dean).

And it’s hard not to think director Bridges and actor Thomas knew exactly what they were doing when Jimmy applies his make-up for the big prank on Frank and Pat and the other couples making out at the cemetery. Bridges lingers on Thomas applying his makeup, having Thomas turn and “reveal” his (true?) self to his friends, the frightened/bold look of apprehension and defiance, and vulnerability, unmistakable in its sexual implications. Unfortunately, Bridges drops this angle entirely.

Equally unsatisfying is Bridges’ inability to fully comment on the culmination of his character Jimmy’s realization that he’s living more inside his own fictitious rendering of Dean hero-worshipping, than in reality. SPOILERS Visiting the horribly burned Billie Jean (she caught on fire in the cemetery, from candelabras she was carrying), laid out like a mummy in her dingy, awful bedroom, he can’t stop recounting how much he aligns with Dean—particularly after seeing Rebel Without a Cause the night before—instead of trying to reach her. He wants absolution from Billie Jean, blaming himself for her accident (it was hardly his fault; Billie Jean was the leader)…but not enough to listen to how self-absorbed and divorced from reality he sounds.

Jimmy’s immersion in the media culture is becoming so complete, he can’t experience events in his life in a pure, unadulterated manner. He states he often feels like he’s “moving in a big, big movie!” and that that feeling is more real, than reality itself. Poor, pathetic Billie Jean, however, knows true reality now, versus the movie reality she used to hide in and revere. She wails, “I’m scarred for life!” and wants none of Jimmy’s self-absorbed hero-worshipping bullshit now.

When the permanent reality of Billie Jean’s tragedy finally hits Jimmy, when he realizes what her life is going to be from now on—and when he no doubt sees she’s no longer the exciting, adventurous, dramatic kook who captivated him—he runs out of her house like it was on fire. Living in a movie haze is far more comforting than facing the often harsh, uncomfortable true reality of life.

Unfortunately, Bridges undercuts this pivotal character revelation by giving Jimmy a sentimental send-off, dressing him in full Dean Rebel regalia, including a motorcycle, and having him kiss-off Charlotte and Hanley at the Homecoming ceremonies. Sneering at the squares and revving his engine to drown out the national anthem, he powers out of town, to go to Hollywood and meet the friends of Dean. This ending should be ironic. Jimmy is no hero; he’s a deluded kid who’s running from reality, not towards some manufactured Hollywood context. And yet, he’s given a big, sentimental, heroic, cinematic valediction with his cool clothes, sweet ride, and defiant anti-hero attitude as he figuratively flips off the square life he hated…which totally subverts and undermines the whole point of September 30th, 1955.

Read more of Paul’s movie reviews here. Read Paul’s TV reviews at our sister website, Drunk TV. Visit Paul’s blog, Mavis Movie Madness!…but mostly TV.

I remember seeing this on TV under yet another title, 24 Hours of the Rebel.

LikeLike