“You guys have been watching too many moving picture films.”

By Paul Mavis

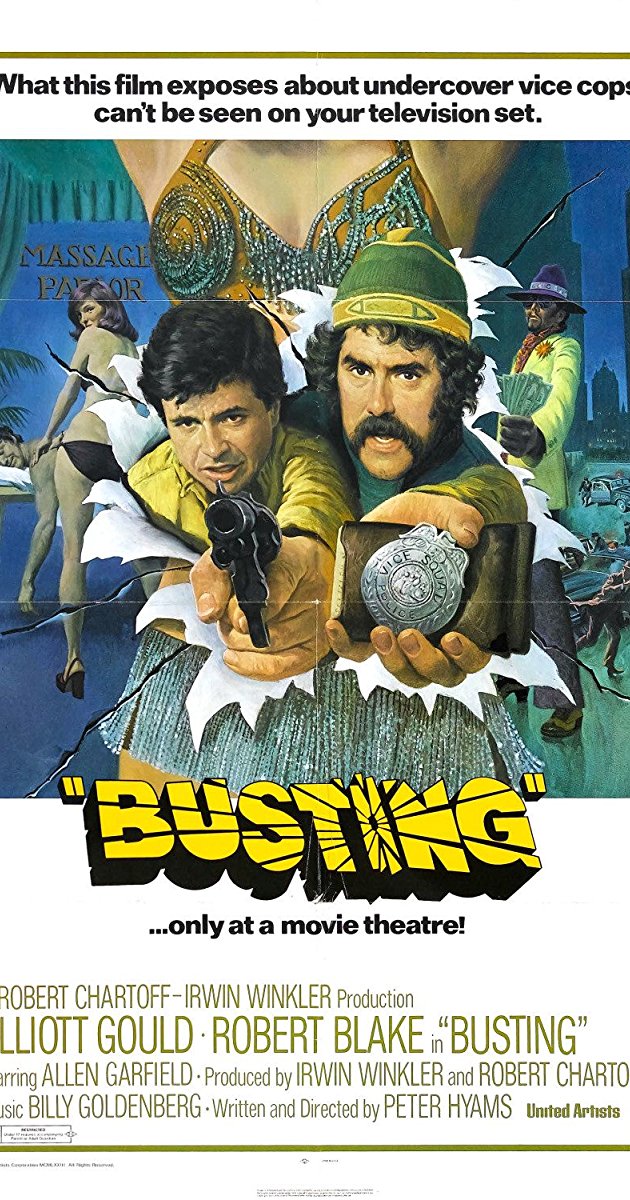

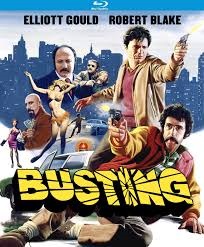

An overlooked, neglected gem from the violent, cynical ’70s—one of the best cop movies ever. Kino Lorber, in the top tier of DVD releasing companies, recently released on Blu-ray Busting, the 1974 buddy cop actioner from United Artists, written and directed Peter Hyams, and starring Elliott Gould, Robert Blake, Allen Garfield, Antonio Fargas, Michael Lerner, and Sid Haig. Hyams creates a dyspeptic, sordid world where everyone is either on the take or afraid to speak up, and where the efforts of two crusading cops don’t amount to squat. Terrifically exciting and completely depressing in equal doses, with two knockout lead performances, Busting‘s suffocating pessimism about “law and order” is relentless entertainment.

Click to order Busting on Blu-ray at Amazon.

L.A. Vice detectives Keneely and Farrel (Elliott Gould and Robert Blake) know they have a solid bust with gorgeous, high-priced hooker Jackie Faraday (Cornelia Sharpe). They’ve been tapping her phone for a month, and now they need her latest trick, Dr. Berman, D.D.S. (Logan Ramsey), who just nailed Jackie in his dentist chair, to set up Keneely as a trustworthy new client. They bust Jackie, and begin to wreck her apartment until she coughs up her little black appointment book…filled with the names of prominent L.A. citizens, including some in the D.A.’s office.

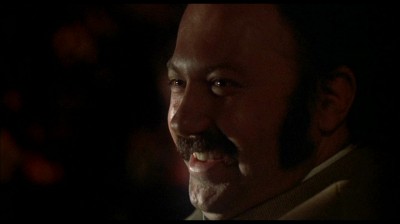

Before you know it, Keneely and Farrel are hauled into their superior’s office, Sergeant Kenefick (John Lawrence), where it is strongly suggested they lie under oath to sabotage their case against Jackie. You see, to satisfy the higher-up officials who answer to slimy gangster Carl Rizzo (Allen Garfield)―who has about everyone on the payroll―this case needs to just…go away. To bring home the point as to whom is really in charge, Keneely and Farrel start pulling some dirty duty, including busting a rough-and-tumble gay bar and watching out for perverts in a public park’s toilet. Aware that they’re increasingly isolated in the department, they decide to work off hours to nail Rizzo, hounding him at every turn in the hopes of forcing his hand with an upcoming dope score.

A favorite since I saw it at the drive-in when I was a kid, watching Busting today is even more satisfying, outside of its terrific action that grabbed me as a kid, now that I can see what a tough balancing act Hyams, in his first major big-screen assignment, pulled off in making an exciting police thriller that’s also so cynically depressing (certainly one should factor in help from Busting’s veteran producers Robert Chartoff and Irwin Winkler, responsible up to that time for gritty, intelligent hits like They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?, The New Centurions, and The Mechanic).

Criminally not nearly as well known as its comedic doppelganger from that same year, director Richard Rush’s delightfully droll Freebie and the Bean (is it racist? Sure…and who cares?), Busting came out in February of 1974 to little business and mixed critical reception, while Freebie and the Bean, sporting two arguably “hotter” box office stars (James Caan and Alan Arkin), and reportedly held up for a later releasing date so as not to compete with Busting, opened in December where it quickly became one of Warner Bros.’ biggest hits of the year (although the pissy critics liked it even less than Busting). Having just watched Freebie and the Bean for the umpteenth time a few weeks ago, it’s easy to see why audiences would go for that deliberately goofy speedball, while staying away from the blackly funny but morose, futile Busting.

Produced and released at the approaching nadir of American cynicism and depression over the developing Watergate scandal and the ongoing Vietnam crisis, Busting‘s gestalt is pure early ’70s American pessimism for anything that smacks of authority or “establishment.” What separates Busting from other cop movies at that time that looked askance at the then-current state of law and order in America, such as Dirty Harry (where Harry had to watch helplessly as the courts sided with the attackers rather than the victims), is that Keneely and Farrel have no one on their side: not the courts, not the public, not even their own police force. No one has their back.

RELATED | More 1970s film reviews

They’re completely alone in their commitment to following the law, with a growing, numbed shock of realization that even their brothers-in-arms―their fellow cops―are actively working with the criminals to, at the very least, humiliate them…if not to get them killed outright (“We’re so fucking alone on this thing it ain’t even a joke,” Blake dejectedly says to a zoned-out Gould). Rizzo runs the show, and through his pay-offs to the higher-ups in politics, the courts, and the police department, he can get any of Keneely and Farrel’s busts written off without a ripple of complaint from the lower men on the totem pole who have to answer to their own corrupt superiors, or lose their jobs (the team’s immediate superior says he has one job: pick up his phone that’s connected to the higher-ups and answer, “Yes, sir,” to anything that’s said).

Everything in Busting is illegal and corrupt. When Keneely and Farrel bust the gorgeous hooker Jackie (lynx-eyed beauty Cornelia Sharp, looking socko in the buff), all it takes is a “someone made a phone call” threat from their immediate superior, and they know the jig is up. They ignore the Sergeant’s suggestion they change their testimony (the sergeant who’s smoking illegal mail-order Cuban cigars), but when they find that Jackie’s little black book has been replaced with a fresh, clean one down at the Evidence Desk, Keneely finally sees how deep the fix goes (“He knows, everybody knows!” he disgustedly taunts, as he throws the counterfeit book at the on-the-take evidence sergeant, played to perfection by the gruff Richard X. Slattery). With the evidence destroyed by their very own, Keneely and Farrel no longer have a case, and Gould has to “throw” his testimony on the stand, to his own deep shame (Gould gets to do a bit of “Elliott Gould shtick” after this scene, leaving the courtroom and giving a sardonic, hallelujah reading of “The Pledge of Allegiance” before attacking a pimp who laughs at him).

Even the crooks look at Keneely and Farrel with dulled astonishment that they’re stupid enough to buck the system that’s in place. When they go to bust a porno shop that features prostitution and drug dealing in the back, manager Marvin (the delightfully weasely Michael Lerner), who spots the undercover Farrel as a cop the second he walks in, chides Blake with a school marmish, “You know you’re not supposed to come in here.” He’s unafraid to name his protector (“Rizzo won’t like that,”) because he knows Rizzo is immune. Keneely and Farrel can’t even get the crooked evidence sergeant to get a warrant to search Marvin’s place for drugs, because the crooked cop obstinately stalls them by insisting he’s not going to wake the judge up at 1:00am. So Keneely and Farrel search anyway (precipitating the movie’s pulse-pounding central chase scene), and once they have the perps trapped in a building, the back-up they called for (two measly uniforms are sent) deliberately let the crooks go, forcing an enraged Keneely to call them “pigs” (when Keneely forces the issue about the uniformed officers, their superior refuses to hear the complaint).

In screenwriter Hyams’ world, Keneely and Farrel aren’t even allowed the solace of self-denial in their efforts to bust Rizzo; they know they’re completely ineffectual as vice officers because all the other cops are actively working with the criminals (Blake sneers, “Big tough cops,” as he commiserates with Gould about how they can’t even keep the hookers off the streets because Rizzo gets them released immediately). Busted down to humiliating toilet duty to catch perverts in the park, Keneely and Farrel still stay on Rizzo (“We sure made mincemeat outta him,” Farrel fatalistically jokes after they fail to shake the gangster during a threatening interview)…but he just laughs at them, openly mocking them for their gung-ho idealism, because he’s already in solid with the authorities (“What’s funny is, you guys really think you’re doing something,” Rizzo jeers).

The ending MAJOR SPOILERS drives this point home brilliantly, with Rizzo, well and truly busted for dealing drugs in his hospital room, laughing at a disbelieving Keneely as he lays out exactly how’s he’s going to beat Keneely’s bust. Director Hyams’ freeze-frame ending on Gould’s pissed-off face, with the soundtrack flash-forwarding to ex-cop Keneely applying for a civilian job, leaves absolutely no room for the audience to celebrate anything Gould or Blake did during the movie. It was all for nothing. The concept of “law and order” simply doesn’t exist if you can just buy it off.

Busting‘s production design matches its dyspeptic moral outlook, with cinematographer Earl Rath (lots of noted TV assignments, like Go Ask Alice and Gargoyles), pushing the grain and fuzzy, diffused lighting through a sea of grimy greens and yellows and reds and blacks. Director Peter Hyams, who also worked in television prior to this first assignment, immediately establishes his penchant for kinetic action sequences with several remarkable set pieces here, particularly the astounding central chase that has Rath’s camera wildly dollying down narrow hallways as criminals run past and then back in front of the camera, blasting guns as the visual schematic takes front-and-back as well as lateral movement—you never see that kind of organic fourth-wall movement—the excitement level rising with the help of that sick, funky groove theme by noted composer Billy Goldenberg (Rath isn’t using Steadycam here…because it wasn’t on the market yet, but you might think so since the dollying is so perfect).

Hyams takes the chase to L.A.s’ famed Farmer’s Market, where he slows the dollys down as Gould and Blake stalk the criminals, with terrified on-lookers crouching in frozen fear as Hyams sinuously glides his camera along the crowded stalls. It’s a remarkable, wholly original-looking sequence, much imitated over the years by other directors who unfairly got credit for the stylization (Hyams would elaborate on this technique in his other films, most notably in the sci-fi remake of High Noon, Outland, where Sean Connery has a similarly exciting foot chase), and it’s bolstered by Hyams’ sure hand in keeping Busting exciting throughout…even when its central message is such a profound downer.

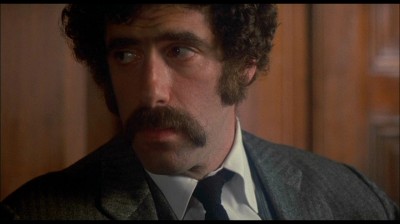

As for the leads, Gould and Blake are an inspired, if deliberately low-key, pairing. Busting came at an interesting period in their careers. Top-billed Elliott Gould, having captured the critics’ and the public’s imagination with his quirky, non-traditional movie star looks and charm in big hits like Paul Mazursky’s Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice and Robert Altman’s M*A*S*H, was by 1974 completely overexposed, running through too many film projects that were receiving at best mixed reviews from the critics and more worryingly, little response from the public: I Love My Wife, Getting Straight, Little Murders, Who?, a misplaced M*A*S*H retread, S*P*Y*S, and two brilliant but sadly neglected Robert Altman classics, California Split and the noir masterpiece The Long Goodbye (his leading man status in A-list pictures wouldn’t really recover from this period of oversaturation).

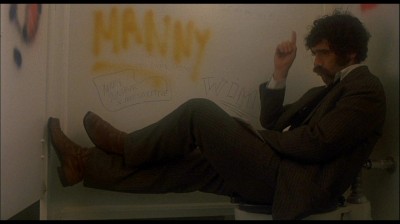

Blake’s position was even more perilous than Gould’s by 1974. Having scrabbled his way back from early fame as a kid performer in the Our Gang comedies, and, after working through anonymous supporting roles in films like A Town Without Pity, PT 109, and The Greatest Story Ever Told, Blake had hit the critical big time in 1967 with his masterful lead work in Richard Brooks’ riveting In Cold Blood. Starring roles followed, such as Tell Them Willie Boy is Here and in 1973 (like Gould’s The Long Goodbye), Blake’s own neglected noir classic, Electra Glide in Blue, but his film work was sporadic and unsuccessful at the box office. Indeed, Busting‘s failure would force Blake to return to TV—still a step down back then for a big screen actor—for the most iconic role of his career: Baretta.

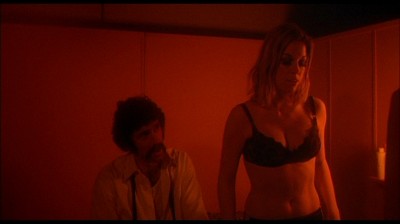

Together, Blake and Gould aren’t excessively cute or even “buddy buddy” acting here; their low-key demeanor is more in keeping with Busting‘s overall tone. They’re consistently amusing, though, with Gould doing his “Groucho Marx-as-basketball-player” bent leg and gum-chewing shtick (Hyams makes sure we get a briefly funny shot of Gould getting a stick during the Farmer’s Market sequence), and Blake acting tough with his unlit cigarette and his little pre-Baretta one-liners. “Film” students (yeech) looking for a quick term paper subject the night before, though, can make a lot out of Hyams’ pushing the boundaries of the subliminal homoerotic underpinnings of the “buddy film” genre when he has the boys here dancing with each other in a gay bar. It’s played for laughs, until Hyams gets serious with a scary bar fight, shot in sick neon red, as the tough drag queens beat the living shit out of Gould and Blake. There have been incoherent complaints, then and now, about this scene being “homophobic,” a toothless invective that’s pretty meaningless at this point (nobody is going to be happy until straight white males disappear off the face of the earth, seems to be the ceaseless clarion call today…).

If there is one small complaint about Busting, it would be that comparative scenes with Blake seem to be missing. We get Gould speaking about his idealism as a young cop, and a good silent sequence of Gould, shamed by his false testimony, going home to his anonymous, cramped apartment and crashing on his sofa bed…but not a glimpse of Blake off-duty (the final freeze-frame also focuses exclusively on Gould’s future fate, not Blake’s). It’s a minor point, though, and one that doesn’t detract from Busting‘s overall significant achievement.

Read more of Paul’s film reviews here. Read Paul’s TV reviews at our sister website, Drunk TV.

Great review of a very underrated film. I thought it was every bit as good as 48 Hrs and better than Lethal Weapon.

LikeLiked by 2 people

We completely agree! Thanks for visiting and chiming in, Eric. It’s much appreciated.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Eric — glad you enjoyed the review! Merry Christmas!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the kind words!

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] the good guy fighting bad guys. Hyams did several cop movies prior to directing it – ”Busting” (1974) and ”Peeper” (1976). So the real question you could ask is whether […]

LikeLike

[…] then followed—cult favorites-but-low-grossers Electra Glide in Blue in ’73 and 1974’s Busting—did zip for him, as well (until TV’s Beretta ultimately resuscitated his […]

LikeLike

[…] Irwin Winkler, prolific as a producer of high-profile films (Rocky, Raging Bull, Casino, Busting), didn’t direct many films in his career but proves a steady hand at pacing a thriller, […]

LikeLike

Nice review of this film—I’d never heard of it until I caught it on TV one night, and wound up getting a VHS of it, since I liked it so much, and because I haven’t seen it on TV since. Surprised that neither Gould nor Blake starred in another film together because they are really an inspired and funny team here. Good film, even if it is your typically downbeat ’70 crime flick.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks-glad you enjoyed the review!

LikeLike