I’ve been saying this for over a week now: if they only had Chuck Heston, George Kennedy, and Marjoe Gortner still in town, that goddamn fire would be out already.

By Paul Mavis

Continuing (a month late…we seriously gotta dry out around here) the reverenced 50th anniversary celebration here at the Movies & Drinks offices of 1974’s year-end release of the Holy Trinity—Airport 1975, Earthquake and The Towering Inferno—it only seems numerically appropriate to next look at Earthquake, which proposed the destruction of Hell-A via the San Andreas fault flipping its lid.

Click to order Earthquake on Blu-ray:

(Paid link. As an Amazon Associate, the website owner earns from qualifying purchases.)

Produced and directed by solid, glossy hitmaker Mark Robson (Peyton Place, Von Ryan’s Express, the sublime Valley of the Dolls), co-written (because the Writers’ Guild of America said so…) by The Godfather‘s Mario Puzo and magazine writer George Fox (with a big uncredited assist from Robson), and starring a heavyweight cast including Charlton Heston, Ava Gardner, George Kennedy, Lorne Greene, Geneviève Bujold, Richard Roundtree, Marjoe Gortner, Barry Sullivan, Lloyd Nolan, Victoria Principal, Walter “Walter Matuschanskayasky” Matthau, and two personal favorites of mine, Jesse and Alan Vint, Earthquake was nothing short of a socko smash with ticket buyers in the winter of 1974.

Earning a worldwide gross equivalent to one billion dollars in today’s inflation-adjusted phony-baloney money, no doubt much of the heat generated at the box office was due to the introduction of Sensurround, a sound process whereby huge speakers would pump sub-audible “infra bass” sound waves into the auditorium at over 120 decibels, to augment the perceptual effects of the movie’s earthquake sequences. Nothing before or since has come close to Sensurround‘s effect on audiences, as anyone who was lucky enough to see Earthquake or the subsequent Sensurround releases, can attest.

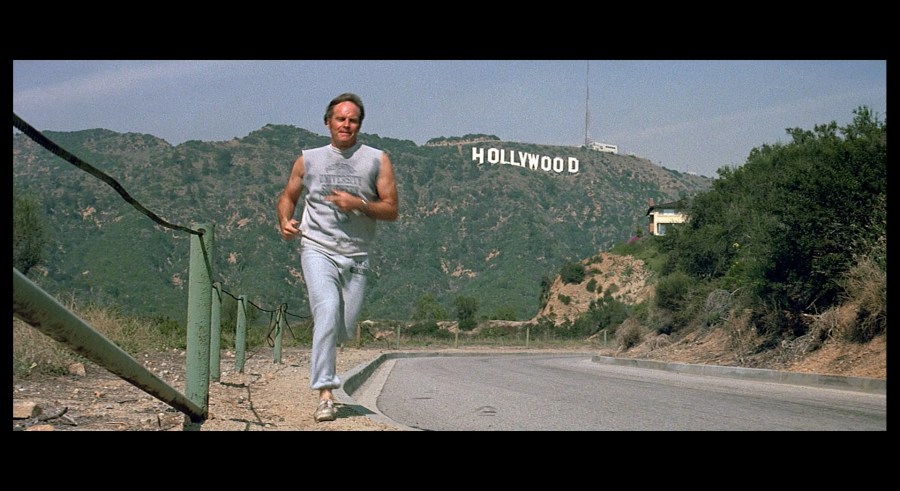

Former college football star and now hotshot Los Angeles engineer Stewart Graff (Charlton Heston) is just trying to keep his beefy, hairy body in shape, with a morning jog and a session on his ancient pulley machine, before his absolute soused harrigan of a wife, Remy Royce-Graff (an absolutely soused harrigan Ava Gardner), starts bitching at him. In particular, she’s livid over Stewart’s a.m. trip to lovely aspiring actress/hot minky widow Denise Marshall (Geneviève Bujold). You see, her stupid kid, Corry (Tiger Williams), wants a game ball from Stewart with Stewart’s, and more importantly, Frank Gifford’s, autographs on it, so what better way for Stewart to come sniffing around some strange than to personally deliver it? I mean the ball.

Wanna know what else makes the whole thing so potentially torrid? Stewart killed her husband. Okay, so actually, Stewart assigned her husband to an engineering job and that killed him…but whatever raises the ‘ol flag pole, right? Well, pickled-in-alcohol Remy isn’t having that shit, so before he leaves, she fakes another suicide attempt (pill overdose. A classic). Too bad that heavy-duty earthquake tremor comes along and conveniently wakes her up stone cold sober and utterly freaked out. And with that, a disgusted, horny Stewart is outta there!

Meanwhile, at the Mulholland Dam, strict protocol says any tremor demands an immediate underwater inspection, but this is Los Angeles, so Izzy Mandelbaum Jr. just goes down in an elevator and comes back up drowned. Inspection…check!

Okay—time out for a Sensurround car chase. So, Officer Bumper Morgan LAPD Officer Lou Slade (George Kennedy) is chasing a car thief who splattered some little kid all over the sidewalk. When Lou busts through Zsa Zsa Gabor’s hedge (I’m not kidding), a Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputy—they’re the mortal enemies of the LAPD—tries to rein-in hot head Lou. Nope—whammo! Lou pops that “peckerwood rich man’s whore” (I’m not kidding), and before you can say, “Rodney King,” he’s suspended.

Still meanwhile, Stewart is beating time with Denise, running lines for her upcoming screen test for an episode of Lucas Tanner (or was it That’s My Mama?), while at the California Seismological Institute (Santa Clara Valley Field Hockey champs, 1931), the guy that married and pushed around Linda Lavin is worried, after that tremor, that a really big one is coming to wipe out L.A.. However, Dr. Willis Stockle (Barry Sullivan), reeking of pipe smoke, tweed, and dashed A-list dreams, says, “Pish posh!” to wife-beater’s concerns. Besides, even if the spousal deadbeat is correct, how the hell are you going to evacuate the City of Angels?

Still still meanwhile…John Shaft, masquerading as Miles Quade, the black Evel Knievel (Richard Roundtree), just knows he can get a big entertainment contract if he can just navigate that big, rickety loop with his motor-sikel. His first attempt? Falls on his head. His manager, Sal Amici (Gabriel Dell)? Worried.

Still still still meanwhile, obviously psychotic grocery store manager Jody Joad (Marjoe Gortner) lets voluptuous Rosa Amici (Victoria Principal), the sister of the manager of the black Evel Knievel (I’m not kidding) have her groceries for free. Jody Joad’s name or Nazis helmets aren’t the worry, so much as him not trimming up the edges of the torn-out magazine pictures of barbell boys pasted all over his pad (bad form, that). He also bitches to Officer Lou about the Hare Krishnas outside his store, driving away business (this is Los Angeles, remember: Officer Lou promptly beats up Gortner). Clearly there’s no respect for National Guard reserve officers like Jody (yep, you can see where that’s going…).

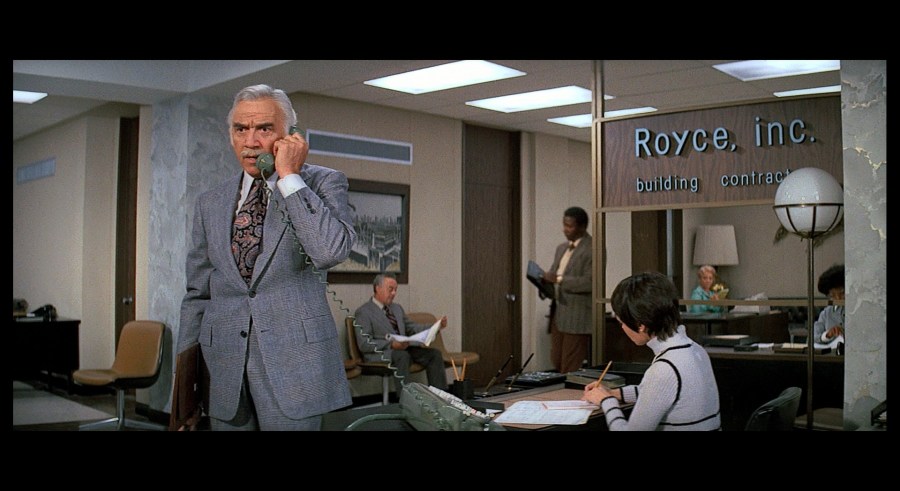

And still still still…oh forget it. Back at Stewart’s office, Remy’s father, Sam Royce (59-year-old Lorne Greene, who fathered 52-year-old Ava Gardner when he was 7…), can absolutely guarantee Stewart that promotion to president of the company…if he just doesn’t go off to that Oregon job and instead sticks around his wife (yep…that bitch Remy called Daddy). Of course this drives Stewart right into Denise’s bed, who promptly gets an invite to Canada. Score!

…and just as all the subplots start to jell and come together, the Big One hits (no, not Heston and Bujold in the sack—that happens off-camera). A 9.9 earthquake on the Richter scale (that’s almost a 10!) devastates Los Angeles County and specifically Los Angeles itself, and now it’s every man and woman and sweaty engineer and even sweatier, jowly cop and stunt rider and rapist National Guardsmen officer and jaw-droppingly stacked looter and really kinda marginally talented foreign (Canadian) actress and plastered desperate housewife and angina pectoris-riddled TV star and drunken stewbum actor making a cameo so his agent gets off his back, for him and herself.

I’m certain I’ve mentioned ad nauseam how I saw Earthquake in original Sensurround (it really was quite a remarkable effect—you felt those bass sound waves go right through you, rearranging your internal organs), and how later I managed the local movie theater were it played, and being shown the structural cracks in the building caused by the system (as well as an abandoned Sensurround speaker and cabinet I should have moved heaven and earth to steal). Well there. I mentioned it again.

Seeing Earthquake at home, no matter how nice Universal’s Blu-ray transfer is, is just a completely different experience than seeing it with Sensurround (and no—you cannot recreate it at home, no matter how close you get to building those horns and speakers—the size of the viewing space alone is wrong, and that right there limits the effect itself, as well as our perception of the effect). I could be like that loser who used to attack me all the time in his “history TV blog” and give you a ton of Wikipedia-lifted info on the process, but why bother (god he was in love with me, and yet so jealous of my talent. Poor boob). You got fingers, right? Look it up yourself.

So without the augmentation of Sensurround, you are left with just…watching Earthquake itself, without “the Event” of Sensurround, as its theater posters so memorably touted. The result? A schizophrenically enjoyable thriller, where the great and awful elements are equally entertaining.

Now that doesn’t mean Earthquake is, overall, a “good” movie, per se (whatever that means). Its main drawbacks—its characters, and many of the performances that bring those ciphers to 2-dimensional life—are egregious enough to add an agreeable amount of unintentional humor to an otherwise solid, A-level action thriller. You can laugh all you want at some of the stiffs staggering around this glossy machine designed to shake ‘n’ bake you, but you can’t deny that its storyline, no matter how chaotically edited, is propulsively watchable (a neat trick for a big movie clocking in over 2 hours long).

Considering Earthquake‘s typically convoluted pre-production, it’s difficult to pinpoint who, exactly, shaped what, when it comes to the screenplay. Universal, having rejuvenated the disaster movie genre with their massive 1970 hit, Airport, was looking for another all-star “line ’em up and watch ’em die” calamity pic. Hiring action director John Sturges to come up with something fast, the close-to-home San Fernando earthquake of February 1971 provided inspiration (indeed, much of the up-lift damage to buildings and surface faulting that resulted from this event, is copied quite closely in Earthquake‘s special effects sequences).

RELATED | More 1970s film reviews

Sturges left the project, though, in early ’72 (to do a terrible Charles Bronson Western), so Universal assigned house producer Jennings Lang to the project, to exec produce, who in turn hired old pro Mark Robson to produce and direct. Lang then hired Puzo, fresh off his megawatt hit, The Godfather, to write a screenplay (for the equivalent of almost one million 2024 dollars)…who then had to bail on the project to work on The Godfather Part II.

At this point, Earthquake may have slipped into limbo, had rival studio Fox not scored a tremendous hit that winter with the all-star disaster epic, The Poseidon Adventure. Seeing those crazy grosses, Universal pushed Earthquake to the front of its development line. Rather inexplicably, they hired unknown magazine writer George Fox to rework Puzo’s 1st draft (Fox had never written a movie before, so how he got in Universal’s sights is unknown). From the details of the subsequent lawsuits (there are always lawsuits whenever a movie makes a ton of money), producer/director Robson contributed significantly to Fox’s 2nd draft, too.

…all of which means who knows who wrote what (unless you’re staring at archived copies of all the scripts and alterations…and even then, good luck). Contemporary reviews of the movie focused mostly on the effects and the spectacle, and paid scant—and mostly withering—attention to the storyline and script. However, Earthquake‘s sketchy characters and scattershot plotting certainly didn’t violate anyone’s expectations of what should dominate in such a disaster/action extravaganza. Heston, according to his diaries, was well aware of the script’s deficiencies…and just resigned himself to making it for the money (of which he made a shitload, thanks to a hefty percentage deal).

Earthquake‘s characters have the barest minimum of backgrounds sketched out for us, and we’re supposed to hang onto the “types” that are cast to get us through the quake action. Heston is suitably commanding as a professional who can intelligently guide us through the physics of the quake and its aftermath, while importantly remaining an outsider (not a politician or civil servant). Kennedy may be a brawny, angry cop, but he’s on our side since he’s outraged by the traffic victim’s death and gets himself suspended for popping a clueless, insensitive deputy (“the Man” hits “the Man,” so he must be one of “us”). It’s no coincidence that both these heroic “outsiders” are our cynical leads in this Watergate-era disaster outing.

The “villains,” of course are the Establishment figures (the quake, despite killing thousands, comes off as marvelously benign here. Remember: he may be the biggest quake to ever hit SoCal…but he doesn’t have to be). Engineering company owner Greene would have appeased a client that wanted to follow the minimally required building codes for an earthquake zone, unlike Heston, who states flatly he’d rather lose a client’s business than “sell out” to save a buck (later, Heston echoes Paul Newman‘s Towering Inferno humanistic architect, expressing guilt over building “40-story monstrosities” in a quake zone). Greene would also manipulate the career (and happiness) of his second-in-command, just to satisfy his alcoholic daughter’s romantic demands.

Scientist Sullivan (no one sells out faster than a poor scientist…) is more worried about the reputation of his institute, should he make the wrong call about the coming quake, than the millions of residents who face potential catastrophic destruction (he eventually comes around, but it’s too late). The L.A. mayor puts political considerations first, as well, wasting valuable time worrying that escalating the issue to the governor would be awkward because they’re not of the same political party. None of this is complex drama, but it does give a more solid underpinning to our identification with the characters as they stumble about the wreckage.

And quite honestly, isn’t that why we’re watching Earthquake? For the head-banging action, not the legitimacy of the dramaturgy? Critics who lamented that less effort was put into the script than into turning the ticket buyers’ insides into jelly, apparently forgot that spectacle for its own sake is as legitimate an artistic aim as an intimate chamber piece.

And as spectacle, Earthquake still delivers. Even without Sensurround. Crashing around in my seat as George Kennedy crashed around in his black and white 1974 Chevy Bel Air was, admittedly, more fun when my gourd was sonically re-arranged. But it’s still fun to watch (how can you not crack up at Kennedy murdering comic one-liners while his flapping jowls threaten to give his head lift-off?).

The major quake itself is rather slyly begun in, what else, a movie theater, where Victoria Principal watches High Plains Drifter (when the film breaks and starts to melt, the ’74 viewers, seated in similar circumstances, absolutely started to look nervously around…). I wish Earthquake had continued to be that clever, but when all hell starts breaking loose out on Universal’s redressed “New York Street,” crafty self-reflexism isn’t nearly as important as steak ‘n’ potatoes thrills.

Except for one or two brief gore scenes (that lady with the glass in her face is less icky and more laffy, since she’s so bad at acting impaled), Earthquake‘s effects are outsized but remarkably restrained, compared to today’s no holds barred carnage. And strangely, that’s what helps them be more…enjoyable, if you will. We want to enjoy other people’s suffering (that’s the whole raison d’etre of the disaster genre), but it helps to not have it so, hmm…realistic.

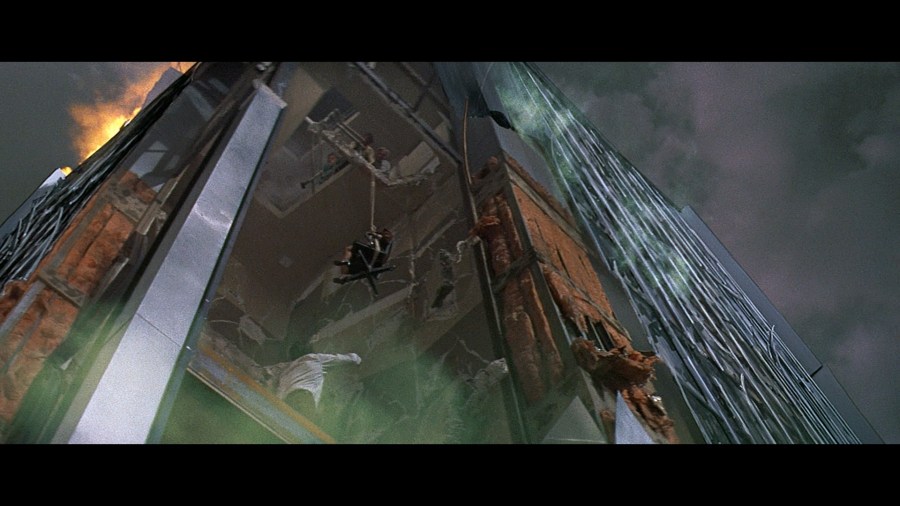

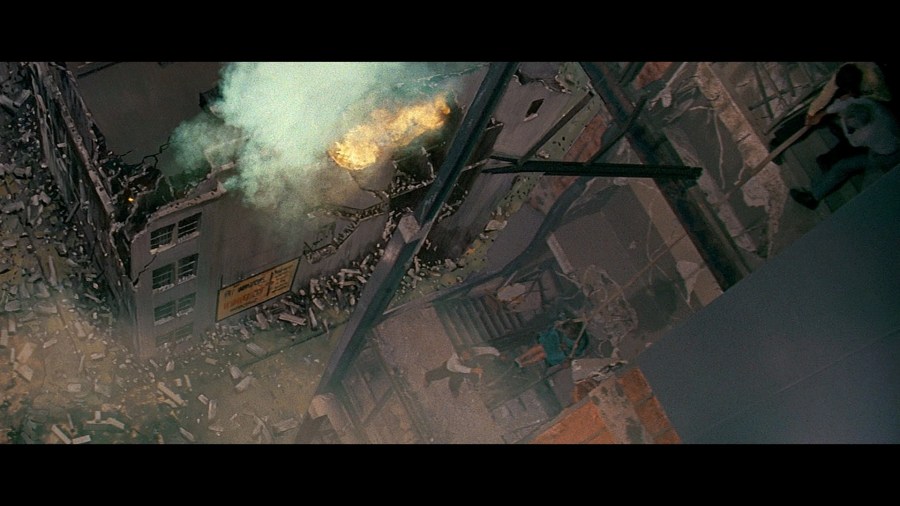

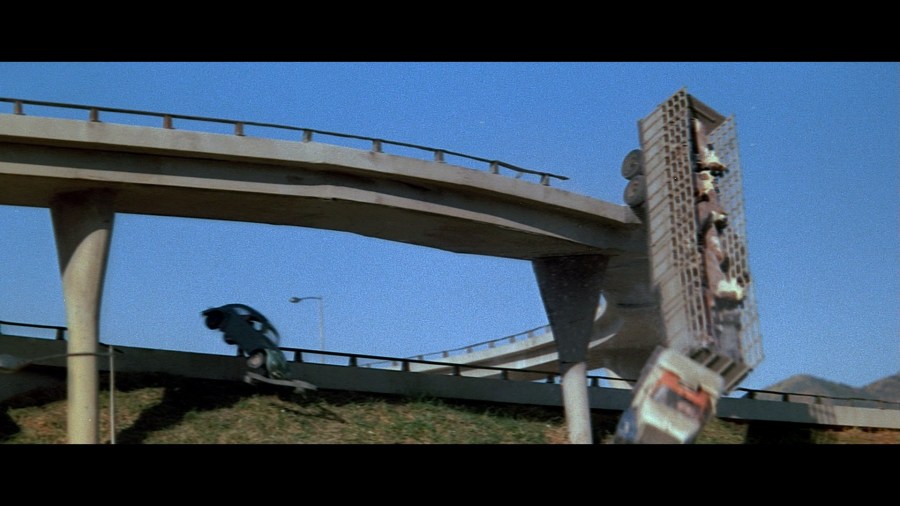

Relying solely on practical and optical effects, Glen Robinson‘s detailed miniatures (shot naturalistically outside by Clifford Stine, in natural light, with real L.A. skylines in the deep backgrounds), practical mechanical effects from Frank Brendel and Jack McMasters (rigged buildings realistically pancaking, with people getting squished by believably huge chunks of styrofoam concrete), and most notably the extensive use of master Universal artist Albert Whitlock’s glass mattes (spectacular in their realism), combine for the absolute top-tier expression of what used to be an artform executed by someone’s skilled hand…not a CGI stylus and a keyboard.

Other than the quake, the central action scene—the partial destruction of Greene’s office building and the rescue efforts of Heston to bring people down via fire hose and office chair—is as good as anything in the “Tiffany” of disaster movies, The Towering Inferno. Whitlock’s extreme, vertiginous p.o.v. mattes of the building, overlaid with filmed smoke effects, are wonders of comic book action framing, while the staging is tense and tight. We even get someone dropping hundreds of feet through a huge plate of glass, like the guy in The Poseidon Adventure.

We get it all in Earthquake; nothing’s cheated. We go from D.W. Griffith-styled melodrama (the entire Bujold subplot, with little Corry, conked into a coma, trapped in the dry Los Angeles River Watershed as the water rushes to meet downed power lines, to Looney Tunes-styled “laughs” such as the man who forgets he’s smoking as he rushes into a gas-filled house to shut off the valve. I particularly liked the Hitchcock-like “god’s eye view” shot of a ceiling collapsing on people below, pitiless in its cold distance.

It’s too bad that when contemporary critics talk about Earthquake‘s effects, they only focus on the one or two misfires, like the twisting skyscraper (I love that effect, achieved by optically printing it on mylar), or the cows that don’t move in the flatbed that goes over the interstate ramp (no defense there…), or most notoriously, the elevator scene, with its optically printed cartoon blood splotches appearing out of the ether to fly up on the screen (reportedly, the original scene as shot was quite bloody; they should have had the guts to leave it in—that effect of everyone hitting the ceiling before impact is awesome). These moments constitute a few seconds of iffy choices in a movie that is overflowing with (then) state-of-the-art—and still quite impressive—special effects.

However, if you just can’t get your head contextually into then-cutting-edge 1974 moviemaking, you can goof on a lot of Earthquake without feeling guilty. Although Earthquake is edited by old pro Dorothy Spencer, who had some classics to her name (including My Darling Clementine, To Be or Not to Be, and Lifeboat), she also put together a lot of unremarkable formula studio work in her career…and certainly the sometimes atrocious editing here is one of Earthquake‘s biggest blunders (my favorite being the disappearance of Richard Roundtree, rescuing Corry, who roars off on his bike, to be forgotten for over half an hour, only to inexplicably reappear again during the last act…before he rides off once more, never to be seen again, his fate…unknown).

Either lost in rewrites, or in the editing, one of the more interesting subplots—psycho National Guardsman Gortner’s taunting by the brothers Vint, before abducting Principal—makes very little sense. I get that Gortner’s a whack job (and another “villain” Establishment figure: a soldier meant to protect the public), but who or what are the Vints? Neighborhood punks? Former employees of Gortner’s? Former customers pissed about their S&H Green Stamps? Schoolboy bullies continuing their mission? Hard to say: they just…appear and disappear, with absolutely no explanation for their existence (Jesse and Alan Vint were far too talented to be slotted in as these figurative cardboard baddies).

But then…Earthquake‘s strong suit isn’t characterizations, nor are the thinly-scripted roles helped by some questionable acting choices. Poor ruined Ava Gardner (god was she talented and beautiful at one time) is the movie’s most conspicuous victim of self-harm; she’s almost the living embodiment of a natural disaster. Pulling a Liz Taylor right from her first scene (God…daaaammit! she brays, her puffy eyes crazy and wild), she’s a road company “Martha” from Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, all snide wisecracks and badly-timed histrionics. When she starts screaming at poor Lloyd Nolan, “Daaahktaaah! Daaahktaaah!”, trying to get help for, “My faaahhthaaa! My faaahhthaaa,” the effect is, sadly, hysterical (Heston, well aware of her shit from 55 Days in Peking, tried hard to have her bounced, but Universal, inexplicably, was adamant on her hiring).

Kennedy’s character comes off broad and gross, as his characterizations usually did, but equally predictable, it’s easy to laugh at him when his character is so often plain wrong in what he’s doing. As the world’s worst motivational speaker, he yells at the wounded and terrified populace surrounding him, looking for leadership, “You’re all gonna have to help yourselves!…move your ass!” (that’ll help!), before he incorrectly tells all the wounded to wait, and wait, and wait, until it’s almost too late to evacuate them to high ground. It’s a blowhard performance of a seriously stupid character.

And while Chuck Heston can do no wrong in my book (don’t like that? Read someone else’s stuff)…he’s strangely stiff and preoccupied here, the realization that he’s merely a cog in a money-making machine all too apparent on his face. I don’t remember how he felt about Bujold (but I can guess what she thought…), but there’s almost no chemistry between them. He looks uncomfortable leering at an actress 19 years his junior when she says the acting part she’s trying out for is a nympho.

We don’t even get a concession to the times: a PG-rated sex scene (he did one in 1970 in Number One, so why so demure?). When Bujold wonders why he made love to her with such…such anger, we’d like to know why, too. Or at least see it. It’s a tantalizing suggestion to his character that’s unfortunately dropped (and by the way, if the last time he played college ball was 16 years before this, he was the world’s only 35-year-old starting Senior).

As for the rest…what can you say? Bujold, a fine, instinctual actress, is completely ground up in the mechanics of the piece, kooky one minute, stupid the next. Lloyd Nolan is popped in for a second to remind us we last saw him to equal non-effect in Airport, while poor Richard Roundtree visibly looks dejected, his Shaft super-fame getting him a big fat nothing in terms of lasting A-list possibilities, just 3 short years later (what a lost opportunity with him).

Certainly the most abused actor is Principal, who screeches convincingly and irritatingly whenever Gortner paws her (Gortner may be the only one who gets this is just pulp—he starts weird and stays there the second he shows up, thank god). Do I have a problem with director Robson having Principal turn full on to the camera and expose her braless breasts to Kennedy and the audience, inviting both to stupidly stare at them (the editor inserts a quick shot of drunk Matthau, dressed like a Hanna-Barbera cartoon character, literally licking his chops like a basset hound)? No, I don’t, frankly. My only beef is how unfunny this supposedly “funny” scene is, and how atrociously it’s staged.

Alas, that’s a lot of Earthquake, however: strange, non-sequitur moments amidst the heavy-duty effects and action. If the quake makes me forget Matthau inexplicably toasting names like, “Peter Fonda!” or “Spiro C. Agnew,” or Heston, in his best hammy growl, dubbing in, “Anywhere…a bar!” when telling Gardner where he’s heading off to, how am I supposed to take Kennedy, in the midst of the action, telling almost-raped Principal that “Earthquakes bring out the worst in some guys, that’s all,” as a means of explaining Gortner’s attack, and comforting her?

With groans like that pinging around the rubble, it’s remarkable that Earthquake rights itself in its final act, and becomes an entirely different movie. As the Mulholland Dam cracks further under the strain of additional aftershocks, the wounded and survivors seeking shelter in the Wilson Plaza parking garage are doomed to drown when it collapses, trapping over 70 people underground. Heston, with Kennedy’s help, volunteers to tunnel through and rescue the survivors.

Unlike anything in either The Poseidon Adventure or The Towering Inferno, the earlier wide-scale destruction of the earthquake scenes are narrowed down and reduced to starkly lit, claustrophobic, inky blacks filling the screen, as Heston, isolated in the frame, works his way through increasingly smaller openings to try and find a way to break through.

RELATED | More Disaster Film Reviews

MAJOR SPOILERS More intense, more intimate, more immediate than all the stuff that preceded it, this frequently nerve-wracking sequence comes out of nowhere in Earthquake, and brings the large-scale destruction down to a frighteningly small area. In his memoirs, Heston said he was hired for this role because of what he represents from previous work: heroic, commanding. We know he’s going to prevail. The semiology of what he represents on the screen, without having to have a single word of dialogue, is brilliantly twisted when, after rescuing over 70 people, he has to make a choice—escape with his life (and to the waiting arms of Bujold), or try and rescue his drowning wife. He chooses the latter…and drowns.

Wait. Heston doesn’t make it? How can that be? Everything in this popcorn movie was pointing to a satisfactory ending where at least something of value—in this case, human heroism and perseverance in the face of overwhelming adversity—prevails. Far more believable than the death of Gene Hackman in The Poseidon Adventure (the audience had no prior associations or investments with newcomer Hackman to just assume he’d make it, along with the poor staging of his death), Heston perishing at the end of Earthquake—an ending the studio hated, and one in which he fought for and won—takes the movie weirdly out of itself.

Suddenly you forget the missteps, the Sensurround, all of it, and you’re left with this nerve-wracking, strikingly shot, ultimately sad little gem of a suspense sequence that seems completely at odds with what you’ve been watching for over an hour and a half. Considering Earthquake‘s overwhelming numbers at the box office, and that old adage about a movie’s success being dependent on its last 10 minutes, I’d like to think audiences were shocked into silence about how much of what they saw in Earthquake was first-rate, unique, a true “event” movie, while forgetting all the prior silliness.

Read more of Paul’s movie reviews here. Read Paul’s TV reviews at our sister website, Drunk TV.

Heston can do no wrong in my book either! Thanks for another thoughtful review–you always manage to convey how well these types of movies work, acknowledging the goofy or dated aspects without mocking them.

My one Sensurround experience was in ‘78–my dad took me to see the theatrical version of Battlestar Galactica. I was 8 years old and obsessed with all things sci-fi, and had missed the 3-hour TV premiere. We took our seats at the old Terrace in North Charleston (not a large, or even state-of-the-art, cinema by any means) and noticed the enormous speakers behind us. Pretty sure these were not ideal Sensurround conditions. The movie started up–it was deafening, and you could feel the vibrations in your chest. We looked at each other and both knew we couldn’t take 2 hours of that, no matter how much I loved the Cylons. To this day, I believe we avoided actual hearing damage by leaving after 5 minutes.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You missed the last one!!

Glad you enjoy the reviews!

LikeLike

[…] whom he bought the land, to pressure Mike to cut corners. Before you can say, “Two tickets to Earthquake Meets The Towering Inferno, please,” a tragedy happens on Christmas Eve, and it’s up to […]

LikeLike